The Nexus of SARS-CoV-2 and Autonomic Dysfunction: A Comprehensive Review of Post-COVID Dysautonomia

Post-COVID dysautonomia, especially POTS, affects millions due to autonomic nervous system disruption. Symptoms include fatigue, brain fog, tachycardia, and GI issues—even after mild infections.

Section 1: The Autonomic Nervous System and Its Dysregulation

The human body is a marvel of intricate, self-regulating systems, many of which operate far below the level of conscious thought. Central to this seamless operation is the autonomic nervous system (ANS), a sophisticated network that functions as the body's master regulator, or "automatic pilot." It tirelessly manages the fundamental processes that sustain life, from the rhythm of the heart to the mechanics of digestion. When this system malfunctions, a condition known as dysautonomia arises, leading to a cascade of debilitating symptoms that can affect nearly every part of the body. Understanding the architecture and function of the ANS, and the nature of its dysregulation, is the essential foundation for comprehending the profound and widespread impact of post-COVID dysautonomia.

1.1 The Body's Automatic Pilot: Anatomy and Function of the ANS

The autonomic nervous system is a critical division of the peripheral nervous system that regulates involuntary physiological processes essential for survival.1 It operates continuously, managing a vast array of functions without conscious effort, whether an individual is awake or asleep.3 Its primary role is to maintain homeostasis—a stable internal environment—by responding to both internal and external stimuli. The reach of the ANS is extensive, with a network of nerves extending from the brain and spinal cord to innervate internal organs, glands, and smooth muscles throughout the body, including the heart, lungs, blood vessels, stomach, intestines, bladder, pupils, and sweat glands.3 This widespread innervation is precisely why its dysfunction can produce such a diverse and multi-systemic array of symptoms.

The architecture of the ANS is primarily defined by two major branches that work in a delicate, opposing balance to modulate bodily functions: the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems.

The Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) is responsible for the body's "fight-or-flight" response.3 It is designed to prepare the body for stressful or emergency situations. When activated, the SNS orchestrates a series of physiological changes to enhance immediate survival capabilities. It increases heart rate and the force of heart contractions, widens the airways to facilitate easier breathing, and stimulates the release of stored energy, primarily glucose, from the liver.4 Concurrently, it diverts blood flow away from non-essential systems, such as the gastrointestinal tract, and toward skeletal muscles, increasing muscular strength. Other characteristic signs of sympathetic activation include pupil dilation, sweaty palms, and the standing of hair on end ("goosebumps").3

The Parasympathetic Nervous System (PSNS), in contrast, governs the "rest-and-digest" functions.3 Its primary role is to conserve and restore the body's energy during periods of calm. The PSNS acts as a brake on the SNS, slowing the heart rate, decreasing blood pressure, and constricting the pupils. It actively stimulates the digestive tract to process food and eliminate waste, and the energy derived from this process is used to build and repair tissues.4 The vagus nerve, the tenth cranial nerve, is a paramount component of the PSNS, providing extensive innervation to the organs of the chest and abdomen and playing a crucial role in regulating heart rate, respiration, and digestion.2

A third, less-discussed but vital component is the Enteric Nervous System (ENS). Often referred to as the body's "second brain," the ENS is a complex mesh-like network of neurons embedded within the walls of the gastrointestinal tract.1 While it is modulated by the SNS and PSNS, it can also function independently to control digestion, including the secretion of enzymes and the coordination of peristalsis, the wave-like muscle contractions that move food through the digestive system.3

The constant interplay between the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches allows the body to adapt seamlessly to changing demands. This balance is what enables heart rate to increase during exercise and decrease during rest, and for digestion to activate after a meal and quiet down during a period of stress. It is the failure of this intricate regulatory balance that defines dysautonomia.

1.2 When Control is Lost: Defining Dysautonomia

Dysautonomia is not a single disease but an umbrella term used to describe a group of medical conditions that result from a malfunction of the autonomic nervous system.7 It is also commonly referred to as autonomic dysfunction or autonomic neuropathy.10 In a state of dysautonomia, the automatic processes controlled by the ANS do not work as they should, leading to a wide range of disruptive, and often debilitating, symptoms.7 The condition is relatively common, affecting more than 70 million people worldwide across all ages, genders, and races.9

Dysautonomia can be broadly categorized into two main types: primary and secondary.

Primary dysautonomia occurs on its own, without an identifiable underlying cause. These forms are often the result of inherited genetic disorders, such as Familial Dysautonomia (a rare condition primarily affecting people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent), or degenerative neurological diseases where the autonomic nerves themselves are the primary site of pathology.10

Secondary dysautonomia, which is far more common, develops as a consequence of another medical condition or injury.10 A wide variety of diseases can damage the autonomic nerves or disrupt their function, including diabetes mellitus (Diabetic Autonomic Neuropathy is likely the most common form of dysautonomia globally), multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, celiac disease, and Parkinson's disease.8 Importantly, viral infections have long been recognized as a significant trigger for secondary dysautonomia, a category into which post-COVID dysautonomia squarely falls. The conceptual framework of secondary dysautonomia is critical because it implies a potentially treatable trigger. Unlike primary forms where the disease process is inherent to the nervous system, in secondary dysautonomia, the autonomic dysfunction is a downstream effect of an underlying cause. This provides a clear target for research and a potential pathway to recovery: if the root cause—be it the inflammatory state, autoimmune response, or viral persistence following COVID-19—can be resolved, the resulting dysautonomia may also improve or resolve entirely.

The clinical presentation of dysautonomia is notoriously heterogeneous, with symptoms that can be mild and intermittent in some individuals, and severe and disabling in others.10 The symptoms are often described as "invisible" because they are not outwardly apparent, and they can affect nearly any system in the body. Common manifestations include balance problems, fainting, nausea, "brain fog" (difficulty with concentration and memory), abnormal heart rates (tachycardia or bradycardia), digestive issues (constipation or diarrhea), fatigue, shortness of breath, palpitations, sleep problems, and temperature intolerance.10

This vast and varied symptom profile creates a formidable diagnostic challenge. The symptoms are non-specific and can mimic many other conditions, most notably anxiety and depression. When a patient presents with fatigue, palpitations, and dizziness, and initial standard medical tests such as basic blood work and an electrocardiogram (ECG) come back normal, their debilitating experience is not validated by objective findings. This mismatch between the severity of a patient's functional impairment and the lack of abnormalities on routine tests frequently leads to misdiagnosis or dismissal of symptoms as psychological in origin.13 Consequently, many patients endure a prolonged and frustrating "diagnostic odyssey," often seeing multiple specialists over several years before receiving an accurate diagnosis, a journey that can itself contribute to significant emotional distress.10

1.3 The Clinical Spectrum of Autonomic Disorders

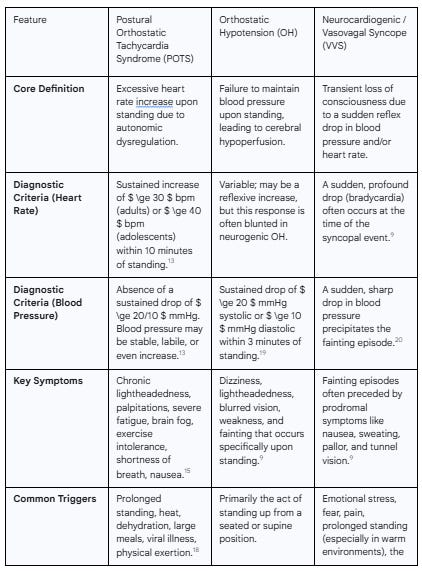

Dysautonomia encompasses at least 15 distinct types of disorders, each with its own characteristic features, though significant symptom overlap is common.9 Understanding the most prevalent forms provides a crucial framework for recognizing the specific phenotypes that are emerging in the post-COVID population. Many of these fall under the category of orthostatic intolerance, a group of conditions where symptoms develop or worsen upon assuming an upright posture and are relieved by lying down.15

Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) is one of the most common forms of dysautonomia, particularly in younger individuals.9 It is defined by a significant and sustained increase in heart rate upon standing, without a corresponding drop in blood pressure. Symptoms are multi-systemic and include lightheadedness, palpitations, profound fatigue, brain fog, and exercise intolerance.14

Orthostatic Hypotension (OH) is characterized by a significant decrease in blood pressure when moving from a lying or sitting position to standing.14 This drop in blood pressure impairs blood flow to the brain, causing symptoms such as dizziness, lightheadedness, blurred vision, and fainting (syncope).9 Neurogenic Orthostatic Hypotension (nOH) is a subtype caused by underlying autonomic nervous system failure and is common in neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson's disease and Multiple System Atrophy.16

Neurocardiogenic Syncope (NCS), also known as Vasovagal Syncope (VVS), is the single most common form of dysautonomia, affecting tens of millions worldwide.8 It is characterized by a sudden, transient loss of consciousness (fainting) caused by a paradoxical reflex that leads to a sharp drop in both heart rate and blood pressure, reducing blood flow to the brain.9 While many individuals may experience a mild case once or twice in their lifetime, severe NCS can cause multiple fainting spells per day, leading to injury and significant disability.8

Other notable forms of dysautonomia include:

Inappropriate Sinus Tachycardia (IST): A condition characterized by an elevated resting heart rate (typically above 100 beats per minute) for no apparent reason, often accompanied by distressing palpitations, fatigue, and dizziness.9

Autoimmune Autonomic Ganglionopathy (AAG): A rare disorder in which the body's immune system produces antibodies that attack and damage receptors on autonomic ganglia, leading to severe autonomic failure.9

Pure Autonomic Failure (PAF): A rare, degenerative disorder of the autonomic nervous system that causes progressive autonomic failure, with orthostatic hypotension being a key feature. It is often associated with the later development of Parkinson's disease or dementia with Lewy bodies.9

Multiple System Atrophy (MSA): A fatal, progressive neurodegenerative disorder that combines features of Parkinsonism with severe autonomic failure. It is a rapidly progressing disease, often leading to patients becoming bedridden within a few years of diagnosis.8

The following table provides a comparative overview of the three most common orthostatic intolerance syndromes, which are frequently diagnosed in the post-COVID population. This comparison helps to clarify the distinct diagnostic criteria that separate these often-confused conditions.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Orthostatic Intolerance Syndromes

Section 2: Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS): A Prototypical Post-Viral Dysautonomia

Among the diverse spectrum of autonomic disorders, Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) has emerged as the most frequently diagnosed form of dysautonomia in patients with Long COVID. To fully appreciate its manifestation in the post-pandemic era, it is essential to first conduct a detailed examination of POTS as it was understood before 2020. This pre-existing knowledge provides a critical foundation, revealing that the link between viral infections and the onset of POTS is not a new phenomenon but a well-established clinical pattern. A deep dive into the pathophysiology, symptoms, and management of "classic" POTS illuminates the framework that clinicians and researchers are now applying to the millions of new patients affected by its post-COVID variant.

2.1 Defining POTS: Criteria, Symptoms, and Patient Experience

POTS is a form of dysautonomia characterized by orthostatic intolerance—the development of symptoms upon assuming an upright posture.15 Its name provides a concise definition of its key features:

Postural (related to body position), Orthostatic (related to standing upright), Tachycardia (an abnormally fast heart rate), Syndrome (a collection of symptoms that occur together).18

The formal diagnostic criteria for POTS are precise and universally accepted: a sustained increase in heart rate of 30 beats per minute (bpm) or more for adults, or 40 bpm or more for adolescents (ages 12-19), that occurs within 10 minutes of moving to a standing position from a supine (lying down) position.13 In many patients, particularly younger individuals, the standing heart rate will exceed 120 bpm.13 A crucial component of this definition is the absence of orthostatic hypotension; there must not be a sustained drop in blood pressure of 20/10 mmHg or more, as this would indicate a different diagnosis.17

The core pathophysiology of POTS is a failure of the autonomic nervous system to properly regulate blood flow against gravity. In a healthy individual, standing up causes about 500-800 mL of blood to shift to the lower body. The ANS immediately compensates by constricting blood vessels in the legs and abdomen and slightly increasing heart rate to ensure adequate blood continues to flow to the heart and brain. In individuals with POTS, this compensatory vasoconstriction is impaired.18 For reasons that are not fully understood, their blood vessels fail to tighten sufficiently in response to autonomic signals. This leads to excessive pooling of blood in the lower extremities and splanchnic (gut) circulation.18 With less blood returning to the heart, stroke volume (the amount of blood pumped with each beat) decreases, threatening perfusion to the brain. To compensate for this deficit and maintain blood pressure, the sympathetic nervous system releases a surge of catecholamines like norepinephrine. While the blood vessels remain unresponsive, the heart—which is typically structurally normal—is highly sensitive to these hormones. The result is a dramatic and sustained increase in heart rate (tachycardia) as the heart works furiously to try and circulate the reduced volume of blood back up to the brain.18

This distinction is of paramount clinical importance. Despite the prominent cardiac symptom of tachycardia, POTS is fundamentally a neurological disorder, not a primary cardiac condition. Patients are often first referred to cardiologists, where extensive cardiac workups, including echocardiograms, reveal a structurally normal heart.18 This can be confusing and frustrating for patients and clinicians alike. The realization that the heart is merely responding appropriately to faulty signals from a dysregulated nervous system is the key to understanding the disease. It correctly redirects diagnostic and therapeutic efforts toward neurology, autonomic medicine, and strategies that target blood volume and nervous system regulation, rather than focusing exclusively on the heart itself.

While the diagnostic criteria focus on heart rate, the patient experience of POTS is defined by a debilitating constellation of multi-systemic symptoms that extend far beyond palpitations. These symptoms are a direct result of cerebral hypoperfusion and sympathetic nervous system over-activation:

Orthostatic Symptoms: The most immediate symptoms upon standing are dizziness, lightheadedness, pre-syncope (a feeling of near-fainting), and in some cases, full syncope (fainting).15

Neurological Symptoms: Perhaps the most disabling symptoms are neurological. Profound, pervasive fatigue that is not relieved by rest is nearly universal. "Brain fog"—a term describing significant difficulties with concentration, short-term memory, and word-finding—is also a hallmark feature.15 Chronic headaches or migraines, shakiness (tremulousness), and severe sleep disturbances are also common.13

Cardiopulmonary Symptoms: Patients frequently experience forceful or racing heartbeats (palpitations), chest pain (often non-cardiac in origin), and shortness of breath, particularly with exertion or upon standing.13

Gastrointestinal Symptoms: The gut is heavily innervated by the autonomic nervous system, and dysfunction is common. Symptoms include nausea, bloating, abdominal pain, early satiety, constipation, and diarrhea.21

Other Manifestations: A classic physical sign is acrocyanosis, a reddish-purple discoloration of the feet and legs upon standing due to the pooling of deoxygenated blood, which resolves upon lying down.13 Other common symptoms include severe exercise intolerance, sensitivity to heat, excessive or reduced sweating, and coldness in the extremities.13

POTS predominantly affects females, with a ratio as high as 5:1, and typically onsets between the ages of 15 and 50.15 A crucial aspect of its epidemiology is that it often begins after a specific physiological stressor or triggering event. These triggers include major surgery, significant physical trauma, pregnancy, puberty, and, most relevant to the current discussion, a viral illness.15 This well-established link to preceding viral infections provides a vital historical context for the explosion of POTS cases seen after COVID-19. The phenomenon is not novel; rather, the pandemic has created a massive-scale example of a known post-infectious syndrome. This allows researchers to leverage decades of prior knowledge on post-viral fatigue and dysautonomia—from triggers like Epstein-Barr virus (mononucleosis) or influenza—to accelerate the understanding of Long COVID.24

2.2 Subtypes and Associated Conditions

POTS is a heterogeneous syndrome, meaning that the same clinical presentation can arise from different underlying pathophysiological mechanisms.17 While these subtypes often overlap and a single patient may exhibit features of more than one, their identification can help guide more targeted treatment. The most commonly described subtypes include:

Neuropathic POTS: This form is associated with a length-dependent, small-fiber peripheral neuropathy.16 The small, unmyelinated nerve fibers that are responsible for signaling blood vessels in the lower limbs to constrict are damaged. This denervation leads directly to impaired vasoconstriction and venous pooling.17

Hyperadrenergic POTS: This subtype is characterized by an excessive release of the neurotransmitter and stress hormone norepinephrine upon standing.16 Patients with this form often have higher standing blood pressure and more prominent symptoms of sympathetic activation, such as tremors, anxiety, and palpitations.16

Hypovolemic POTS: In this form, the central issue is an abnormally low volume of circulating blood (hypovolemia).16 This can be due to dysregulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, which controls fluid and salt balance in the body. The reduced blood volume exacerbates the challenge of maintaining adequate blood flow to the brain when upright.

Furthermore, POTS does not exist in a vacuum. It frequently co-occurs with a cluster of other complex chronic conditions, suggesting shared underlying biological vulnerabilities. The most common comorbidities include:

Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS): A genetic connective tissue disorder characterized by joint hypermobility, skin hyperextensibility, and tissue fragility. The link is thought to be related to laxity in the blood vessel walls, which may contribute to venous pooling.16

Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS): A disorder where mast cells, a type of immune cell, inappropriately release inflammatory mediators like histamine. This can cause a wide range of symptoms, including flushing, hives, itching, gastrointestinal distress, and anaphylaxis, and can directly affect vascular tone and contribute to POTS symptoms.17

Autoimmune Diseases: POTS is more common in individuals with established autoimmune diseases such as Sjögren's syndrome, lupus, and celiac disease, strengthening the hypothesis that an autoimmune process may underlie many cases of POTS.18

2.3 Standard of Care (Pre-COVID)

As a syndrome with no single cause, there is currently no cure for POTS. Treatment is therefore focused on managing the debilitating symptoms, improving functional capacity, and enhancing quality of life.13 The approach is highly individualized and multi-faceted, combining non-pharmacological strategies with medication when necessary.

Non-pharmacological management is the cornerstone of POTS care and is often the first line of treatment:

Volume Expansion: The most critical intervention is to increase circulating blood volume. This is achieved through a high fluid intake, typically 2-3 liters per day, and a high sodium intake of 8-10 grams per day (equivalent to 3-4 teaspoons of salt).13 The increased salt helps the body retain fluid, thereby expanding plasma volume.

Compression Garments: Medical-grade, waist-high compression stockings (30-40 mmHg) or abdominal binders are used to provide external pressure on the lower body. This physically reduces the amount of blood that can pool in the legs and abdomen, promoting its return to the heart.13

Physical Counter-maneuvers: Patients are taught simple isometric exercises that can be performed when feeling lightheaded. These include crossing the legs, clenching the fists, and tensing the muscles in the legs and buttocks. These maneuvers increase venous return and can temporarily raise blood pressure, helping to abort a pre-syncopal episode.21

Rehabilitative Exercise: While exercise intolerance is a major symptom, a carefully structured and gradual exercise program is one of the most effective long-term treatments. Critically, the program must begin with non-upright (reclined or supine) exercises, such as a recumbent bicycle, rowing machine, or swimming.13 This allows the patient to improve cardiovascular conditioning and muscle tone without the added stress of gravity, thereby avoiding the exacerbation of orthostatic symptoms. Over many months, the patient can gradually transition to more upright forms of exercise.

Pharmacological management is reserved for patients whose symptoms are not adequately controlled by non-pharmacological measures. The choice of medication is tailored to the patient's specific subtype and symptom profile:

Fludrocortisone: A mineralocorticoid that promotes sodium and water retention by the kidneys, helping to expand blood volume.13

Midodrine: An alpha-1 adrenergic agonist that acts as a vasopressor, directly causing constriction of blood vessels to reduce venous pooling and increase blood pressure.13

Beta-Blockers: Used in low doses to blunt the excessive tachycardia and reduce palpitations. They are particularly useful in the hyperadrenergic subtype of POTS.13

Pyridostigmine: An acetylcholinesterase inhibitor that can enhance autonomic ganglionic transmission and improve sympathetic vasoconstriction.13

Other Medications: A variety of other drugs, including SSRIs, SNRIs, clonidine, and octreotide, may be used off-label to target specific symptoms or underlying mechanisms.13

Ultimately, the successful management of POTS requires a comprehensive and collaborative approach, often involving a team of specialists including a neurologist, cardiologist, physical therapist, and dietitian, all working with an educated and empowered patient.

Section 3: The Emergence of Dysautonomia in the Wake of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, has reshaped the global health landscape in ways that extend far beyond the acute respiratory illness. As millions of individuals recovered from the initial infection, a new and perplexing clinical entity emerged: a chronic, multi-systemic illness now widely known as Long COVID or Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 (PASC). Within this complex syndrome, a strong and consistent clinical link to dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system has been firmly established.9 Dysautonomia is now recognized not merely as a rare complication but as a prominent and profoundly debilitating manifestation of Long COVID, affecting a significant portion of survivors and presenting a formidable challenge to patients and healthcare systems alike.27

3.1 A New Post-Viral Trigger: The Link Between COVID-19 and Dysautonomia

An accumulating body of clinical observation and scientific research has solidified the connection between a prior SARS-CoV-2 infection and the subsequent new onset of autonomic disorders.20 This post-infectious syndrome can manifest with symptoms that persist for many months or years after the acute illness has resolved, and in some cases, the resulting dysautonomia is expected to be a lifelong condition.30 The autonomic nervous system has been identified as a key target of the virus's long-term pathology, giving rise to a wide spectrum of symptoms that mirror those seen in pre-existing forms of dysautonomia.

This recognition has led to a critical re-evaluation of Long COVID itself. Many of the most common and disabling symptoms of Long COVID—such as pervasive fatigue, cognitive dysfunction ("brain fog"), palpitations, and exercise intolerance—are also the classic, defining symptoms of dysautonomia.10 This significant overlap suggests that autonomic dysfunction is not just one of many disparate components of Long COVID. Instead, it may be a central pathophysiological mechanism that drives a large portion of the entire Long COVID symptom complex. This conceptual shift is vital: it implies that the ANS is a primary site of pathology in Long COVID and that identifying and treating the dysautonomia could be the key to alleviating the most severe aspects of the condition for a large subset of patients. This moves dysautonomia from being considered a mere "complication" to being a potential "core feature" of the disease.

3.2 Prevalence and Patient Demographics

While the exact prevalence of post-COVID dysautonomia is still being determined through ongoing research, initial studies consistently report alarmingly high numbers. One early report found evidence of dysautonomia in nearly 70% of individuals living with the lasting effects of COVID-19.9 More recent and rigorous studies support these high estimates. Research supported by Dysautonomia International suggests that 67% of Long COVID patients develop moderate to severe dysautonomia.28 A 2025 pre-print study utilizing the validated COMPASS-31 autonomic symptom questionnaire found an even higher prevalence, with 82% of its Long COVID cohort screening positive for significant autonomic dysfunction.34

Within the spectrum of post-COVID dysautonomia, Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) appears to be the most common and well-characterized phenotype.36 Estimates suggest that POTS develops in approximately 2% to 14% of all individuals with Long COVID, and its prevalence rises to around 30% in cohorts of highly symptomatic patients.26 Other forms of autonomic dysfunction, such as orthostatic hypotension and inappropriate sinus tachycardia, are also frequently observed.33

A crucial and counterintuitive finding from this research is what can be termed the "mild COVID paradox." The risk of developing severe, long-term dysautonomia is not correlated with the severity of the initial acute COVID-19 infection.26 Individuals who experienced only mild, non-hospitalized cases of COVID-19 are just as likely to develop significant and disabling autonomic dysfunction as those who were critically ill. This decoupling of long-term risk from acute severity has profound public health implications. The global public and policy narrative during the pandemic was understandably focused on preventing severe acute disease, hospitalization, and death. However, this finding reveals a massive, hidden burden of chronic illness emerging from the hundreds of millions of "mild" infections worldwide. This creates a "second public health crisis" of chronic disability that will continue to strain healthcare systems, social support services, and global economies for the foreseeable future.29

3.3 The Symptom Constellation of Post-COVID Dysautonomia

The clinical presentation of post-COVID dysautonomia is heterogeneous, but the symptom profile largely aligns with known autonomic syndromes, with various forms of orthostatic intolerance being the most common presentations.20 The impact on quality of life is substantial, with a large-scale survey finding that at 7 months post-infection, 45.2% of patients with Long COVID had to reduce their work hours, and 22.3% were unable to work at all due to their illness.41

The most commonly reported symptoms can be grouped by the affected physiological system:

Cardiovascular: Patients frequently report inappropriate sinus tachycardia (a resting heart rate that is too fast), heart palpitations (a sensation of a forceful, rapid, or fluttering heartbeat), and labile blood pressure that can fluctuate unpredictably.20 Chest pain or discomfort is also a common complaint.32

Neurological: This domain includes some of the most disabling symptoms. Pervasive and profound fatigue is nearly universal. Cognitive dysfunction, or "brain fog," manifests as difficulty with concentration, memory loss, and poor attention.20 Other common neurological symptoms include chronic headaches, dizziness, and significant sleep disturbances.20

Respiratory: Shortness of breath (dyspnea), particularly with mild exertion, is a frequent symptom, even in patients without significant underlying lung damage from their acute infection.20

Gastrointestinal: The ENS is often affected, leading to a range of digestive issues. These include nausea, vomiting, delayed gastric emptying (gastroparesis), bloating, abdominal pain, and altered bowel habits such as constipation or diarrhea.33

Thermoregulatory and Sudomotor: Patients often experience abnormalities in sweating, such as excessive sweating (hyperhidrosis), and a general intolerance to heat or cold.33

Constitutional: General symptoms such as chronic pain, muscle aches, and a persistent low mood are also significantly associated with the presence of dysautonomia.32

This complex and multi-systemic symptom burden underscores the pervasive role of the autonomic nervous system in maintaining bodily function and highlights the devastating impact its dysregulation can have on an individual's ability to engage in work, school, and daily life.

Section 4: Unraveling the Biological Mechanisms

The question of how a respiratory virus like SARS-CoV-2 can lead to profound and lasting dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system is a central focus of ongoing global research. While a complete picture has yet to emerge, a number of plausible and non-mutually exclusive biological mechanisms have been proposed. These hypotheses paint a picture of a complex, multi-faceted pathological process involving direct viral injury, a dysregulated immune response, and widespread systemic effects that converge to disrupt autonomic control.

4.1 Direct Viral and Inflammatory Insult

Evidence suggests that SARS-CoV-2 can directly damage nervous system tissues, including key components of the ANS. This neuro-invasive potential is a characteristic shared by other human coronaviruses.43

A leading hypothesis centers on vagus nerve inflammation. The vagus nerve is a cornerstone of the parasympathetic nervous system, providing the primary "braking" signal to the heart and regulating lung and gut function. Its proximity to the respiratory tract, the primary site of infection, makes it a plausible target. This hypothesis is supported by compelling postmortem studies of deceased COVID-19 patients, which have detected the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA and an infiltration of inflammatory immune cells, primarily monocytes, directly within the tissue of the vagus nerve.30 Further molecular analysis (RNA sequencing) of these nerve tissues revealed a strong inflammatory response within the neurons, endothelial cells, and supportive Schwann cells, with the intensity of this response correlating with the amount of viral RNA detected. This suggests a dose-dependent inflammatory process that could lead to axonal dysfunction and impaired nerve signaling.30

The vagus nerve emerges as a critical anatomical locus of pathology because its dysfunction can single-handedly explain many of the core symptoms of post-COVID dysautonomia. Impairment of its parasympathetic function would lead to an unchecked "fight-or-flight" state, resulting in tachycardia (loss of the vagal brake on the heart), gastroparesis (impaired vagal control of digestion), and respiratory irregularities. Furthermore, the vagus nerve mediates the body's "inflammatory reflex," a key pathway for controlling systemic inflammation. Damage to this nerve could therefore contribute to the uncontrolled inflammation seen in both acute and long-form COVID-19.42 This makes the vagus nerve a central node connecting the viral, inflammatory, and autoimmune hypotheses and a highly attractive target for future diagnostics and therapeutics.

More broadly, the neurotropism of SARS-CoV-2 allows it to invade the central nervous system (CNS) through several potential routes:

Neuronal Route: The virus may infect peripheral nerves, such as the olfactory nerve in the nasal cavity (explaining the common symptom of anosmia, or loss of smell) or the vagus nerve in the lungs, and then travel in a retrograde fashion along the nerve axon to enter the brainstem.43

Hematogenous (Bloodstream) Route: During the viremic phase of acute infection, the virus can circulate in the blood and cross the protective blood-brain barrier (BBB). This may occur through direct infection of the endothelial cells that form the barrier or via a "Trojan horse" mechanism, where the virus infects circulating immune cells like monocytes, which then carry it across the BBB.43

Once in the CNS, the virus or the inflammation it incites could cause direct damage to autonomic control centers located in the brainstem and hypothalamus. These brain regions are the "central command" for the entire ANS, and damage to them could fundamentally disrupt the top-down regulation of heart rate, blood pressure, and other vital functions.42

4.2 The Autoimmune Hypothesis

A strong body of evidence points toward a para-infectious or post-infectious immune-mediated mechanism as a key driver of post-COVID dysautonomia.45 In this scenario, the initial viral infection triggers a dysregulated immune response that begins to mistakenly attack the body's own tissues—a process known as autoimmunity.

Several theories exist as to how this occurs. One is molecular mimicry, where antibodies produced to fight the SARS-CoV-2 virus may cross-react with proteins on the surface of human cells that bear a structural resemblance to viral proteins. If these human proteins are part of the autonomic nervous system, such as receptors on autonomic ganglia or nerves, these autoantibodies could bind to them and block or otherwise impair their normal function.20 Another possibility is that the intense, widespread inflammation during the acute infection leads to a loss of immune self-tolerance, causing an overactive immune system to launch a direct attack on components of the ANS.20

This autoimmune hypothesis is supported by several lines of evidence. First, traditional POTS is known to have a strong association with established autoimmune diseases like lupus and Sjögren's syndrome.18 Second, studies in pre-pandemic POTS patients have identified the presence of various functional autoantibodies that target adrenergic and muscarinic receptors—key signaling molecules in the ANS.17 Finally, ongoing research is actively investigating the hypothesis that post-COVID POTS is a T-cell mediated autoimmune disorder, similar in nature to conditions like rheumatoid arthritis.33

4.3 Systemic Contributors to Autonomic Dysfunction

Beyond direct viral or autoimmune damage to the nervous system, the systemic chaos induced by COVID-19 can also contribute to autonomic dysfunction through several interconnected pathways.

Sympathetic and Cytokine Storms: In severe acute COVID-19, the body can enter a state of extreme sympathetic nervous system over-activation, termed a "sympathetic storm." This massive release of stress hormones contributes to and is exacerbated by a "cytokine storm," a flood of pro-inflammatory molecules.45 This vicious cycle of hyper-inflammation and sympathetic overdrive can cause widespread organ damage, including to the delicate autonomic nerves, while simultaneously inhibiting the anti-inflammatory effects of the parasympathetic system.42

Endothelial Dysfunction: A hallmark of severe COVID-19 is endotheliitis, or widespread inflammation and damage to the endothelial cells that line all blood vessels.43 Healthy endothelium is crucial for regulating vascular tone (the constriction and dilation of blood vessels). Widespread endothelial dysfunction can impair the ability of blood vessels to constrict properly in response to autonomic signals, directly contributing to the venous pooling that underlies orthostatic intolerance syndromes like POTS.27

Renin-Angiotensin System (RAS) Imbalance: The SARS-CoV-2 virus uses the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as its primary receptor to enter human cells. ACE2 is a critical component of the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), which plays a central role in regulating blood pressure and fluid balance. By binding to and causing the downregulation of ACE2, the virus can create a profound imbalance in the RAS. This disruption can lead to an excess of the vasoconstrictor angiotensin II and a deficit of vasodilators, impairing cardiovascular regulation and weakening parasympathetic tone.42

Persistent Viral Reservoirs: A growing body of research suggests that in some individuals, viral particles, RNA, or proteins may persist in various tissues (such as the gut) for months after the acute infection has cleared.27 These "viral reservoirs" could act as a chronic source of antigenic stimulation, perpetuating a state of low-grade inflammation and immune dysregulation that continues to damage the nervous system long after the initial illness is over.27

The existence of these multiple, plausible mechanisms strongly suggests that post-COVID dysautonomia is not a single, uniform disease. It is likely a heterogeneous condition with several different underlying endotypes. For example, one patient's POTS may be driven primarily by autoantibodies, while another's may be the result of direct vagal nerve damage, and a third's may stem from persistent endothelial dysfunction. This has profound implications for treatment, as a "one-size-fits-all" approach is unlikely to be effective. The future of treating this condition will depend on identifying biomarkers that can stratify patients into these mechanistic subgroups, allowing for the development of targeted, personalized therapies—such as immunotherapy for autoimmune cases or neuromodulation for those with primary nerve injury.

Section 5: Clinical Evaluation and Diagnostic Pathways

The diagnosis of post-COVID dysautonomia can be challenging due to its "invisible" nature and the wide overlap of its symptoms with other conditions. However, a systematic clinical evaluation, moving from a detailed patient history to objective, quantifiable tests of autonomic function, can lead to an accurate diagnosis. This process is not only crucial for guiding treatment but also serves as a vital tool for validating the patient's experience. Providing objective physiological proof of their condition can help overcome the diagnostic bias that often leads to the dismissal of their symptoms as psychological, thereby legitimizing their illness and facilitating access to appropriate care and support.

5.1 Patient History and Symptom Assessment

The diagnostic journey begins with a comprehensive patient history. The clinician must elicit a detailed timeline, specifically focusing on the onset and evolution of symptoms in relation to the patient's acute SARS-CoV-2 infection.10 Key areas of inquiry include:

The Orthostatic Nature of Symptoms: It is critical to ask specifically how symptoms change with posture. Questions like, "Do your dizziness, brain fog, or palpitations get worse when you stand up or after standing for a while?" and "Do they improve when you sit or lie down?" are essential for identifying orthostatic intolerance.

Multi-System Review: A thorough review of systems is necessary to capture the full scope of potential autonomic dysfunction, covering cardiovascular, neurological, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, thermoregulatory, and secretomotor (e.g., dry eyes/mouth) domains.19

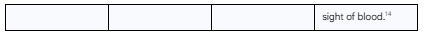

To standardize and quantify the symptom burden, validated questionnaires are an invaluable tool. The Composite Autonomic Symptom Scale 31 (COMPASS-31) is a widely used, 31-item self-report survey that screens for and measures the severity of autonomic symptoms across six domains: orthostatic intolerance, vasomotor, secretomotor, gastrointestinal, bladder, and pupillomotor.20 A total score is calculated, and a cutoff score of greater than 16.4 or 20.0 is often used to suggest the presence of moderate to severe autonomic dysfunction.28 The COMPASS-31 is not only useful for initial screening but can also be used to track symptom changes and response to treatment over time.

5.2 Bedside and Clinical Autonomic Testing

Following a suggestive history, the next step is objective testing to document the physiological abnormalities.

Orthostatic Vitals (Active Stand Test): This is the most fundamental and accessible diagnostic test, which can be performed in any clinical office.37 The procedure involves measuring the patient's blood pressure and heart rate after they have been lying down (supine) for at least 10 minutes to establish a baseline. The patient then stands up, and measurements are repeated at intervals, typically at 1, 3, 5, and 10 minutes of standing.13 This simple test can readily diagnose clear cases of POTS (by documenting the requisite heart rate increase without a blood pressure drop) or orthostatic hypotension (by documenting the requisite blood pressure drop).19

Tilt-Table Test (TTT): The tilt-table test is considered the gold standard for the formal diagnosis of orthostatic intolerance syndromes.13 During this test, the patient lies flat on a mechanized table and is secured with safety straps. After a period of supine rest, the table is tilted to an upright angle of 60 to 70 degrees, and the patient remains in this passive, head-up position for up to 45 minutes.19 Heart rate and blood pressure are continuously monitored throughout the test. The key advantage of the TTT is that it eliminates the contribution of the skeletal muscle pump in the legs, which can sometimes mask or compensate for autonomic dysfunction during an active stand test. This provides a purer assessment of the autonomic nervous system's ability to respond to gravitational stress and can confirm a diagnosis of POTS, orthostatic hypotension, or provoke a vasovagal syncopal event in a controlled setting.15 A positive tilt-table test provides undeniable physiological evidence of a patient's condition, which is often a turning point in their diagnostic journey.

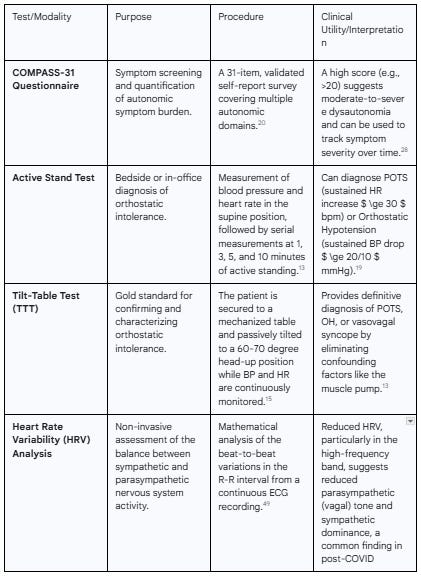

Table 2: Diagnostic Modalities for Post-COVID Dysautonomia

5.3 Advanced Autonomic Function and Neuropathic Assessment

For a more detailed characterization of autonomic dysfunction or when the diagnosis remains unclear, patients may be referred to a specialized autonomic laboratory for a battery of advanced tests.

Heart Rate Variability (HRV): This is a non-invasive technique that analyzes the subtle variations in time between consecutive heartbeats (the R-R interval on an ECG). A healthy heart does not beat like a metronome; it has a high degree of variability, which reflects a healthy, adaptable autonomic nervous system with strong parasympathetic (vagal) tone. A reduction in HRV is a well-established marker of autonomic dysfunction, indicating a shift toward sympathetic dominance and a withdrawal of parasympathetic influence. Studies have consistently found reduced HRV in patients with Long COVID, providing objective evidence of their underlying autonomic imbalance.31

Sudomotor (Sweat) Testing: Since the nerves that control sweating are part of the autonomic nervous system, testing sweat function can provide a window into autonomic nerve integrity. The Quantitative Sudomotor Axon Reflex Test (QSART) is a highly specialized test that measures the volume of sweat produced in response to chemical stimulation. A reduced sweat response can be an objective sign of damage to the small autonomic nerve fibers, confirming a small fiber neuropathy.10

Cardiovagal and Adrenergic Baroreflex Testing: Tests like the Valsalva maneuver (forced exhalation against a closed airway) and deep breathing exercises are used to assess the integrity of the baroreflex, the crucial reflex arc that maintains stable blood pressure. The characteristic patterns of heart rate and blood pressure change during these maneuvers can reveal specific deficits in sympathetic or parasympathetic function.50

Small Fiber Neuropathy Biopsy: When a small fiber neuropathy is suspected as the underlying cause of a patient's symptoms (particularly in cases of neuropathic POTS), a skin biopsy can provide a definitive anatomical diagnosis. A small sample of skin is taken from the leg and specially stained to allow for the direct visualization and counting of the small epidermal nerve fibers. A reduced nerve fiber density confirms the diagnosis.13

A particularly striking finding from quantitative autonomic testing has highlighted the severity of this post-viral condition. A 2023 study directly compared the results of a full battery of autonomic tests between post-COVID patients, healthy controls, and patients with Pure Autonomic Failure (PAF), a rare and progressive neurodegenerative disease.50 The results showed that, after adjusting for age and sex, the degree of autonomic dysfunction in the post-COVID cohort was comparable in severity to that seen in patients with PAF.50 This is a powerful and sobering finding. It demonstrates that the biological insult from SARS-CoV-2 can produce a level of measurable autonomic failure on par with a known, severe neurodegenerative disease. This objectively quantifies the severity of post-COVID dysautonomia, placing it firmly in the category of a serious neurological disorder and arguing forcefully against any attempts to trivialize it as mere "fatigue" or a psychological issue.

Section 6: Management and Therapeutic Interventions for Post-COVID Dysautonomia

Currently, there is no definitive cure for post-COVID dysautonomia. However, this does not mean the condition is untreatable. A comprehensive, multi-disciplinary management approach that combines non-pharmacological strategies, carefully tailored rehabilitation, and symptomatic medications can lead to significant improvements in symptoms and functional capacity. The overarching goal of these interventions is not to eradicate a single pathology but rather to support the dysfunctional autonomic nervous system, reduce physiological stressors, and restore a state of autonomic balance, thereby giving the body a chance to recalibrate and heal.

6.1 Foundational Non-Pharmacological Strategies

These lifestyle-based interventions form the bedrock of management for all patients with post-COVID dysautonomia and are often sufficient to produce meaningful improvement.

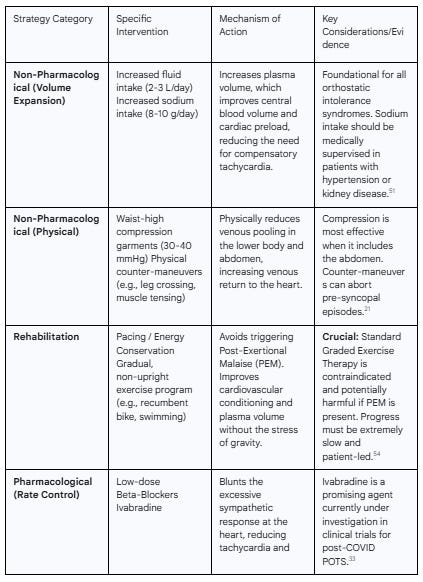

Patient Education and Reassurance: This is the critical first step in management. Many patients have been through a long and invalidating diagnostic process. Explaining the physiological basis of their symptoms—that their tachycardia, for example, is a real response to blood pooling—can alleviate anxiety and empower them to become active participants in their care.51 Providing access to reliable educational resources is also essential.29

Volume Expansion: Increasing the volume of circulating blood is one of the most effective strategies for improving orthostatic tolerance. This is achieved through a dual approach:

Increased Fluid Intake: Patients are typically advised to consume 2-3 liters of water or other non-caffeinated fluids throughout the day.51

Increased Sodium Intake: Liberalizing salt intake to 8-10 grams per day helps the kidneys retain fluid, thereby expanding plasma volume. This can be achieved by adding salt to food or using salt tablets, though this should be done in consultation with a physician, especially for patients with a history of hypertension or kidney disease.51

Dietary Adjustments: The timing and composition of meals can significantly impact symptoms. Patients are advised to eat small, frequent meals rather than large ones to avoid postprandial hypotension, a drop in blood pressure caused by the diversion of blood to the gut for digestion.51 It is also recommended to avoid or limit the intake of caffeine and alcohol, as both can exacerbate tachycardia and dehydration.21

Compression Therapy: The use of medical-grade compression garments is a simple and effective physical method to combat venous pooling. Waist-high compression stockings or tights with a pressure of 30-40 mmHg, or an abdominal binder, can physically squeeze blood out of the lower body and back into central circulation, improving blood return to the heart and brain.51

Sleep Hygiene: Sleep disturbances are a core feature of dysautonomia and a major contributor to fatigue. Establishing a strict sleep routine—going to bed and waking up at the same time every day, even on weekends—is crucial.22 Optimizing the sleep environment to be cool, dark, and quiet is also important. Additionally, elevating the head of the bed by 6 to 10 inches (by placing blocks under the bedposts, not just using extra pillows) can help reduce nocturnal diuresis and conserve fluid volume overnight, which may alleviate morning symptoms.22

6.2 Pacing and Rehabilitative Exercise

The approach to exercise and activity in post-COVID dysautonomia requires a fundamental paradigm shift away from traditional rehabilitation models. The central concept that must guide all activity is the recognition and management of Post-Exertional Malaise (PEM). PEM is a pathological worsening of symptoms that occurs after physical, cognitive, or emotional exertion. It is characterized by a delayed onset, often appearing 12 to 48 hours after the triggering activity, and can lead to a severe "crash" that lasts for days or weeks.54 PEM is a hallmark of post-viral illnesses like Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) and is now recognized as a core feature in a significant subset of Long COVID patients.54

Crucially, PEM is not the same as deconditioning or simple fatigue. Applying conventional Graded Exercise Therapy (GET), which encourages patients to progressively "push through" their fatigue, is not only ineffective but can be profoundly harmful to individuals with PEM, leading to a long-term worsening of their baseline health.54 The failure to distinguish PEM from deconditioning is a primary cause of iatrogenic harm in this patient population.

Therefore, the cornerstone of safe and effective rehabilitation is Pacing. Pacing involves learning to live within one's "energy envelope" by carefully planning and prioritizing activities, breaking tasks into manageable segments, and incorporating frequent, pre-emptive rest breaks throughout the day.52 The goal is to avoid the "boom-and-bust" cycle of overexertion followed by a crash. Patients may use activity diaries or heart rate monitors to identify their personal triggers and limits.

Once a patient has stabilized their symptoms through pacing and the foundational strategies, a very gradual and structured rehabilitative exercise program can be initiated. This must follow specific principles to avoid triggering orthostatic stress or PEM:

Start with Non-Upright Exercise: The program must begin with exercises performed in a seated or lying-down position, such as a recumbent exercise bike, a rowing machine, or swimming.51 This allows for the improvement of cardiovascular tone, muscle strength, and plasma volume without the gravitational challenge of being upright. Protocols like the modified CHOP or Levine protocol provide a structured framework for this approach.54

Go Low and Slow: The intensity and duration of exercise must start very low and be increased extremely gradually over a period of many months, always staying well within the limits that do not trigger PEM.

6.3 Pharmacological Approaches

When non-pharmacological interventions are insufficient, medications may be added to target specific symptoms. The use of these medications is often off-label, based on clinical experience from treating traditional forms of dysautonomia, and must be highly individualized.

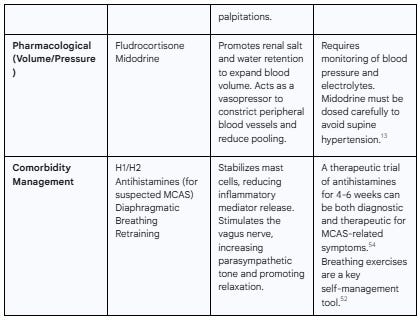

For Tachycardia Control: Low-dose beta-blockers can be used to blunt the excessive heart rate response and reduce the sensation of palpitations. Ivabradine, a medication that specifically lowers heart rate at the sinoatrial node without affecting blood pressure, is emerging as a promising option and is being actively investigated in randomized controlled trials for post-COVID POTS.33

For Volume and Pressure Support: Fludrocortisone is a mineralocorticoid that helps the body retain salt and water, thereby increasing blood volume. Midodrine is a vasopressor that directly constricts peripheral blood vessels, reducing venous pooling and helping to maintain blood pressure upon standing.

For Neuromodulation: Medications that act on the nervous system, such as pyridostigmine, can enhance autonomic signaling. Low-dose Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) or Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) may also be used to help modulate central autonomic control.53

Investigational Therapies: Given the suspected immune component, various immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory drugs are being explored. These include low-dose naltrexone, the HIV medication maraviroc, and in severe, refractory cases, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG).33

6.4 Management of Comorbidities

Effective management also requires addressing the frequently co-occurring conditions that can contribute to the overall symptom burden.

Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS): If symptoms like flushing, hives, itching, and severe gastrointestinal distress are prominent, MCAS may be a contributing factor. A diagnostic trial of H1 antihistamines (e.g., cetirizine, loratadine) and H2 antihistamines (e.g., famotidine, cimetidine) for a period of several weeks can be both diagnostic and therapeutic.54

Breathing Pattern Disorders: Many patients develop dysfunctional breathing patterns, such as shallow upper chest breathing, which can exacerbate anxiety and feelings of breathlessness. Breathing retraining with a focus on slow, diaphragmatic (belly) breathing can help calm the nervous system by stimulating the vagus nerve, thereby increasing parasympathetic tone and promoting a state of relaxation.52

The management of post-COVID dysautonomia is an active and evolving field. A patient-centered, holistic approach that integrates these various strategies provides the best opportunity for symptom control, functional improvement, and long-term recovery.

Table 3: Summary of Management Strategies for Post-COVID Dysautonomia

Section 7: Prognosis and Future Directions

As the world moves beyond the acute phase of the pandemic, the long-term consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection, particularly the development of chronic conditions like dysautonomia, are becoming a primary focus of public health and scientific inquiry. The prognosis for individuals with post-COVID dysautonomia is a critical question for millions of affected patients, while the unprecedented scale of this post-viral phenomenon offers a unique and powerful opportunity to advance our understanding of all post-infectious illnesses. The path forward requires a clear-eyed assessment of the long-term outlook, a contextualization of this new syndrome within the history of post-viral disease, and a focused research agenda to address the most urgent unanswered questions.

7.1 The Long-Term Outlook

The long-term prognosis for post-COVID dysautonomia is currently characterized by uncertainty and variability.26 For many, the condition appears to be chronic. Symptoms can be unpredictable, fluctuating from day to day, and may be exacerbated by stressors such as other illnesses, physical overexertion, or emotional distress.26 One 2021 study reported that symptoms persisted in 85% of participants at a follow-up of 6 to 8 months post-infection, suggesting a high potential for chronicity.26 Some experts believe that a subset of patients may face a lifelong condition requiring ongoing management.30

However, the outlook is not universally bleak. Other research has indicated a more hopeful trajectory, with one pre-pandemic study suggesting that approximately half of individuals with post-viral dysautonomia recovered within a period of 1 to 3 years.26 Clinical experience with the post-COVID cohort suggests that with an early and accurate diagnosis followed by comprehensive, multi-disciplinary treatment, many individuals report at least some degree of symptomatic improvement.29 Furthermore, some objective data suggests that the "noxious effect" of COVID-19 on autonomic control may naturally fade over time in some patients, as indicated by improvements in heart rate variability on follow-up testing.49

The prognosis for any given individual is likely influenced by a complex interplay of factors, including the specific underlying mechanism of their dysautonomia (e.g., autoimmune vs. neuropathic), the presence of comorbidities, and, critically, their access to timely and appropriate medical care. The reality for many patients is that long wait times to see autonomic specialists—often 6 to 12 months or more—create significant delays in diagnosis and treatment.29 This suggests that the prognosis is not merely a biological question but is also a healthcare logistics problem. The biological potential for recovery on a 1-3 year timeline may exist, but the actual patient experience may be one of prolonged illness due to systemic barriers to care. Improving the healthcare system's capacity to diagnose and manage this condition could therefore directly improve patient outcomes and shorten recovery times.

7.2 Post-COVID Dysautonomia in Context: Comparison with Other Post-Viral Syndromes

The emergence of dysautonomia after COVID-19 is not a novel biological event but rather a massive-scale manifestation of a long-observed pattern of post-viral illness. There is a profound and striking overlap in the symptoms and proposed pathophysiology between post-COVID dysautonomia and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS), a debilitating chronic illness that is also frequently triggered by acute viral infections, such as the Epstein-Barr virus.25

Both conditions are characterized by a core symptom cluster of profound fatigue, post-exertional malaise (PEM), cognitive dysfunction ("brain fog"), unrefreshing sleep, and chronic pain.25 Furthermore, autonomic dysfunction is a well-documented feature of ME/CFS, with a high prevalence of POTS and evidence of small fiber neuropathy, mirroring the findings in the Long COVID population.25

While the clinical pictures are remarkably similar, some initial comparative studies have suggested potential differences in the severity and pattern of autonomic dysfunction. One 2023 study found that a cohort of ME/CFS patients reported a higher burden of autonomic symptoms on the COMPASS-31 questionnaire and exhibited more significantly reduced heart rate variability compared to a cohort of post-COVID patients.25 This could suggest that ME/CFS represents a more severe or entrenched state of autonomic dysregulation, though more research is needed to confirm these findings.

The COVID-19 pandemic, while a global tragedy, has inadvertently created an unprecedented research opportunity that may ultimately solve the long-standing crisis of ME/CFS. For decades, ME/CFS patients have been medically neglected, underfunded, and their illness often dismissed as psychological, partly due to the lack of a single, universal trigger and the heterogeneity of the patient population. The pandemic has now generated a massive, parallel cohort of millions of Long COVID patients with an almost identical clinical presentation but with a known and indisputable infectious trigger.25 The sheer scale of the Long COVID crisis has forced the global scientific and medical establishments to take post-viral illness seriously, attracting unprecedented levels of research funding and attention.33 The biological discoveries now being made in Long COVID—regarding autoimmunity, viral persistence, endothelial dysfunction, and autonomic neuropathy—are directly applicable to the long-standing hypotheses in ME/CFS. It is highly probable that a breakthrough in understanding or treating post-COVID dysautonomia will also represent a breakthrough for ME/CFS and other post-viral conditions, potentially leading to the first effective, evidence-based treatments for a group of illnesses that have languished in scientific obscurity for years.

7.3 Unanswered Questions and the Research Agenda

Despite the rapid progress made in understanding post-COVID dysautonomia, critical knowledge gaps remain. The path forward must be guided by a focused research agenda aimed at answering the most pressing questions that will directly impact patient care.

Key unanswered questions include:

What are the specific risk factors and biomarkers that can predict which individuals will develop dysautonomia after a SARS-CoV-2 infection?

What are the precise autoimmune targets (e.g., specific receptors or nerve proteins) in patients with an autoimmune form of the condition?

Why does the condition persist for years in some individuals while resolving in others? What are the biological markers of recovery?

What is the definitive role of persistent viral reservoirs, and can antiviral therapies be effective in treating the condition?

To address these questions, future research priorities must include:

Longitudinal Cohort Studies: Establishing and following large, diverse cohorts of post-COVID patients over many years is essential to fully understand the natural history of the condition, identify predictors of prognosis, and document long-term outcomes.

Mechanistic and Interventional Trials: Research must move beyond observational studies and symptomatic treatments to randomized controlled trials that test therapies targeting the underlying pathophysiology. This includes trials of immunomodulatory agents (e.g., IVIG, monoclonal antibodies), antivirals, and drugs aimed at correcting endothelial dysfunction or RAS imbalance.27

Biomarker Discovery: A concerted effort is needed to identify and validate reliable biological markers that can be used to objectively diagnose dysautonomia, stratify patients into mechanistic subgroups for personalized treatment, and monitor their response to therapy.27

Healthcare System Improvement: Research and resources must also be directed at improving clinical care pathways. This includes developing and disseminating educational resources for community-based healthcare professionals to enable them to recognize, diagnose, and manage less complex cases at the local level. This is crucial for reducing the overwhelming burden on the small number of existing autonomic specialty centers and ensuring that patients receive timely care.29

Conclusions

The evidence is clear and compelling: infection with SARS-CoV-2 can, and frequently does, cause dysautonomia. This post-viral syndrome is a prominent, debilitating, and potentially chronic feature of Long COVID, affecting millions of individuals worldwide. It is characterized by a malfunction of the autonomic nervous system, leading to a multi-systemic array of symptoms, with Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) being the most common presentation. The underlying mechanisms are complex and likely involve a combination of direct viral nerve damage, autoimmune processes, and systemic inflammation. While the prognosis is variable, a multi-faceted management approach focused on volume expansion, pacing, targeted rehabilitation, and symptomatic medication can significantly improve quality of life. The unprecedented scale of this crisis, while devastating, has ignited a new era of research into post-viral illness that holds the promise of not only providing answers for those suffering from Long COVID but also for the millions who have long suffered from related conditions like ME/CFS. The challenge ahead is to translate this growing scientific understanding into effective treatments and accessible clinical care for all who are affected.

Acknowledgement

I acknowledge the use of Gemini AI in the preparation of this report. Specifically, it was used to: (1) brainstorm and refine the initial research questions; (2) assist in writing and debugging Python scripts for statistical analysis; and (3) help draft, paraphrase, and proofread sections of the final manuscript. I reviewed, edited, and assume full responsibility for all content.

Works cited

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539845/#:~:text=The%20autonomic%20nervous%20system%20is,sympathetic%2C%20parasympathetic%2C%20and%20enteric.

Anatomy, Autonomic Nervous System - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539845/

Autonomic Nervous System: What It Is, Function & Disorders - Cleveland Clinic, accessed August 26, 2025, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/23273-autonomic-nervous-system

Overview of the Autonomic Nervous System - Brain, Spinal Cord, and Nerve Disorders, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/brain-spinal-cord-and-nerve-disorders/autonomic-nervous-system-disorders/overview-of-the-autonomic-nervous-system

Autonomic nervous system - Wikipedia, accessed August 26, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Autonomic_nervous_system

Autonomic nervous system - Queensland Brain Institute, accessed August 26, 2025, https://qbi.uq.edu.au/brain/brain-anatomy/peripheral-nervous-system/autonomic-nervous-system

my.clevelandclinic.org, accessed August 26, 2025, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/6004-dysautonomia#:~:text=Dysautonomia%20is%20a%20nervous%20system,work%20properly%2C%20causing%20disruptive%20symptoms.

People living with various forms of dysautonomia have trouble regulating these systems, which can result in lightheadedness, fainting, unstable blood pressure, abnormal heart rates, malnutrition, and in severe cases, death., accessed August 26, 2025, http://www.dysautonomiainternational.org/page.php?ID=34

Dysautonomia: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment - WebMD, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.webmd.com/brain/dysautonomia-overview

Dysautonomia: What It Is, Symptoms, Types & Treatment - Cleveland Clinic, accessed August 26, 2025, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/6004-dysautonomia

Dysautonomia - Wikipedia, accessed August 26, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dysautonomia

Other Forms of Dysautonomia, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.dysautonomiainternational.org/page.php?ID=35

Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia ... - Dysautonomia International, accessed August 26, 2025, http://www.dysautonomiainternational.org/page.php?ID=30

What are some different types of dysautonomia? - MedicalNewsToday, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/types-of-dysautonomia

Postural Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/postural-tachycardia-syndrome-pots

Forms of Dysautonomia, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.dysautonomiasupport.org/forms-of-dysautonomia/

Defining Cardiac Dysautonomia – Different Types, Overlap Syndromes; Case-based Presentations - PMC, accessed August 26, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7533131/

Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) - Johns Hopkins Medicine, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/postural-orthostatic-tachycardia-syndrome-pots

TABLE 1: Diagnostic criteria for common autonomic disorders., accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.aapmr.org/docs/default-source/news-and-publications/covid/covid-blitshteyn-multi-disciplinary-tables-1222.pdf?sfvrsn=92702a7c_0

The connection between dysautonomia and long COVID - Providence blog, accessed August 26, 2025, https://blog.providence.org/blog/the-connection-between-dysautonomia-and-long-covid

Postural tachycardia syndrome (PoTS) - NHS, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/postural-tachycardia-syndrome/

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) - Cleveland Clinic, accessed August 26, 2025, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/16560-postural-orthostatic-tachycardia-syndrome-pots

Decoding the Mysteries of Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome | NHLBI, NIH, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/news/2021/decoding-mysteries-postural-orthostatic-tachycardia-syndrome

After COVID: Understanding POTS and Dysautonomia - The Fascia Institute, accessed August 26, 2025, https://fasciainstitute.org/after-covid-understanding-pots-and-dysautonomia/

Dysautonomia and small fiber neuropathy in post-COVID condition ..., accessed August 26, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10648633/

Dysautonomia after COVID: Is there a connection?, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/dysautonomia-after-covid

Post-COVID Dysautonomia: A Narrative Review of Pathophysiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Emerging Management Strategies | Sciety, accessed August 26, 2025, https://sciety.org/articles/activity/10.31219/osf.io/2tvmk_v1

Study finds 67% of individuals with long COVID are developing dysautonomia, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.news-medical.net/news/20220501/Study-finds-6725-of-individuals-with-long-COVID-are-developing-dysautonomia.aspx

Long-Covid Autonomic Dysfunction - The Dysautonomia Project, accessed August 26, 2025, https://thedysautonomiaproject.org/long-covid-autonomic-dysfunction/

Vagus nerve inflammation contributes to dysautonomia in COVID-19 ..., accessed August 26, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10412500/

What are the implications of autonomic testing for a patient who has recently recovered from Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and is now experiencing issues with balance and dexterity?, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.droracle.ai/articles/142646/pt-recently-recovered-from-covid-now-reporting-issues-with-balance-and-dexterity-wonders-about-automonic-testing-tell-me-more-abotu-this

Autonomic dysfunction and post–COVID-19 syndrome: A still elusive link - PubMed Central, accessed August 26, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8712711/

Long COVID Research Fund - Dysautonomia International, accessed August 26, 2025, https://dysautonomiainternational.org/page.php?ID=282

Dysautonomia in long COVID is prevalent and could explain the frequency of symptoms, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.03.24.25324564v1.full-text

Dysautonomia in long COVID is prevalent and could explain the ..., accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.03.24.25324564v1

Dysautonomia in COVID-19 Patients: A Narrative Review on Clinical Course, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Strategies - PubMed Central, accessed August 26, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9198643/

Management of POTS due to Long COVID - AAFP, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/afp-community-blog/entry/management-of-pots-due-to-long-covid.html

Post-COVID POTS vs. Traditional Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome: Key Differences in Symptoms and Treatment - Leapcure Blog, accessed August 26, 2025, https://blog.leapcure.com/post-covid-pots-vs-traditional-pots-key-differences-in-symptoms-and-treatment/

Strong Link Found Between Long COVID and Dysautonomia - Austin Neuromuscle, accessed August 26, 2025, https://austinneuromuscle.com/strong-link-found-between-long-covid-and-dysautonomia/

COVID-19 and POTS: Is There a Link? | Johns Hopkins Medicine, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/coronavirus/covid19-and-pots-is-there-a-link

Dysautonomia in COVID-19 Patients: A Narrative Review on Clinical ..., accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9198643/

Prevalence and patterns of symptoms of dysautonomia in patients with long‐COVID syndrome: A cross‐sectional study - PubMed Central, accessed August 26, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9110879/

review on pathogenesis of nervous system SARS-CoV–2 damage - NEUROLOGY OF COVID–19 - NCBI Bookshelf, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK579780/

Vagus nerve inflammation contributes to dysautonomia in COVID-19 - PubMed, accessed August 26, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37452829/

Covid-19-Induced Dysautonomia: A Menace of Sympathetic Storm - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed August 26, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8586167/

Mechanisms by Which SARS-CoV-2 Invades and Damages the Central Nervous System: Apart from the Immune Response and Inflammatory Storm, What Else Do We Know? - MDPI, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/16/5/663

Investigating the possible mechanisms of autonomic dysfunction post-COVID-19 - PMC, accessed August 26, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9789535/

Cardiovascular and autonomic dysfunction in long-COVID syndrome and the potential role of non-invasive therapeutic strategies on cardiovascular outcomes - Frontiers, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/medicine/articles/10.3389/fmed.2022.1095249/full

Investigating autonomic nervous system dysfunction among patients with post-COVID condition and prolonged cardiovascular symptoms - Frontiers, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/medicine/articles/10.3389/fmed.2023.1216452/full

Abstract 4144056: Quantitative Testing Reveals Severity of Autonomic Dysfunction after Acute COVID-19 Infection: A Comparison with Controls and Autonomic Failure, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/circ.150.suppl_1.4144056

Autonomic dysfunction in 'long COVID': rationale, physiology and management strategies, accessed August 26, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7850225/

Dysautonomia in long COVID – Rotherham Doncaster and South ..., accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.rdash.nhs.uk/services/long-covid/dysautonomia-in-long-covid/

Treatments for Long COVID autonomic dysfunction: a scoping review - PubMed, accessed August 26, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39658729/

Long COVID & Dysautonomia - APTA, accessed August 26, 2025, https://www.apta.org/contentassets/b59f3f3c026449e5bd5f79ab679d43dd/long-covid--dysautonomia-evidence-based-rehabilitation-strategies.pdf