The Long Shadow of SARS-CoV-2: Lasting Molecular and Epigenetic Alterations in Brain Glial Cells

Long COVID causes lasting glial dysfunction via chronic neuroinflammation and epigenetic reprogramming, disrupting brain support systems and impairing cognition, mood, and neural repair.

Executive Summary

The global emergence of SARS-CoV-2 has been followed by a significant public health crisis involving the long-term sequelae of the infection, collectively known as Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) or Long COVID. A substantial proportion of individuals, including those who experienced only mild acute illness, suffer from debilitating and persistent neurological symptoms, most notably cognitive dysfunction or "brain fog," chronic fatigue, and mood disorders. This report synthesizes a growing body of evidence to elucidate the long-term molecular and functional alterations in three critical glial cell populations of the central nervous system (CNS)—microglia, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes—following SARS-CoV-2 infection. The central thesis of this analysis is that the neuropathology of Long COVID is primarily driven by a state of sustained, glial-mediated neuroinflammation, often independent of widespread, productive viral replication within the brain parenchyma.

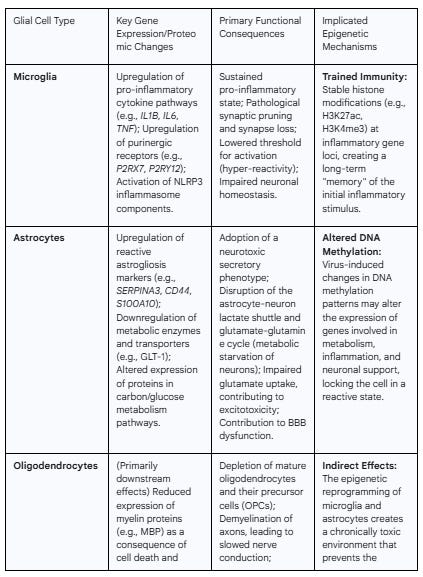

The investigation reveals distinct, cell-specific pathological responses. Microglia, the brain's resident immune sentinels, are chronically activated by persistent viral components, such as the spike protein. This activation results in a transcriptomic shift towards a pro-inflammatory state, characterized by the upregulation of cytokine pathways and the dysregulation of purinergic signaling, leading to pathological synaptic pruning and impaired neuronal homeostasis. Astrocytes, which serve as a preferential target for direct viral infection, undergo a profound transformation into a state of reactive astrogliosis. This is accompanied by a dramatic metabolic reprogramming that disrupts critical neuro-supportive functions, such as the astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle, and the adoption of a secretory phenotype that is directly toxic to neurons. Oligodendrocytes and the integrity of myelin sheaths appear to be collateral damage within this hostile neuroinflammatory milieu. The combined effects of pro-inflammatory cytokines and reactive microglia lead to oligodendrocyte depletion, impaired function of their precursor cells, and subsequent demyelination, which compromises the efficiency of neural circuit communication.

Crucially, this report posits that these long-lasting pathological states are not merely a failure of inflammation to resolve but are actively maintained by durable epigenetic reprogramming of the glial cells themselves. The concept of "trained immunity"—an epigenetic memory of an inflammatory stimulus—provides a compelling molecular mechanism for the sustained hyper-reactivity of microglia. Emerging evidence of altered DNA methylation and histone modifications in both peripheral immune cells of Long COVID patients and in CNS cells following viral challenge suggests that the initial infection creates a form of "epigenetic scarring." This process effectively "locks in" a dysfunctional, pro-inflammatory gene expression program in glial cells, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of neuroinflammation and neuronal injury that underlies the chronic nature of neurological Long COVID. Understanding these cell-specific molecular and epigenetic mechanisms is paramount for the development of targeted therapeutic strategies aimed at resetting glial homeostasis and alleviating the long-term neurological burden of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Section 1: The Neuropathological Landscape of Post-Acute SARS-CoV-2 Infection

1.1. Clinical Manifestations: Characterizing the "Brain Fog" and Cognitive Sequelae

The long-term neurological effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection represent a substantial and growing public health concern, with a significant fraction of survivors experiencing a constellation of symptoms long after the resolution of the acute illness.1 This condition, formally known as Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) and colloquially as "Long COVID," is characterized by a diverse array of enduring symptoms, including cognitive impairment, fatigue, sleep disturbances, persistent headaches, and mood disorders.1 Meta-analyses of numerous studies have begun to quantify the profound burden of these neurological sequelae. For instance, the overall prevalence of cognitive impairment in individuals post-COVID-19 has been estimated at 27.1%, with rates increasing to 33.1% for follow-up periods greater than 12 months.1 Similarly, persistent depression and anxiety affect an estimated 14.0% and 13.2% of individuals, respectively, with prevalence rates for both conditions rising to over 18% beyond one year post-infection.1 Other common complaints include dizziness (16%), memory impairment, sleep difficulties, and olfactory dysfunction.1

A critical aspect of the clinical picture is that these debilitating long-term symptoms are not confined to patients who experienced severe, hospitalized COVID-19. Indeed, prevalence rates for cognitive impairment, depression, and anxiety are often highest among outpatients who presumably had milder acute infections.1 This observation is fundamental, as it suggests that the underlying pathophysiology is not necessarily linked to the systemic severity of the initial disease, such as profound hypoxia or multi-organ failure. Instead, it points toward more subtle, persistent biological mechanisms that can be triggered even by a mild respiratory illness.6 The symptom cluster, particularly the pervasive "brain fog" characterized by deficits in attention, memory, and executive function, bears a striking resemblance to other post-viral syndromes and even to the neurological symptoms observed after mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), suggesting the possibility of convergent biological pathways centered on neuroinflammation and diffuse neural circuit disruption.3 The nature of these clinical manifestations—being predominantly functional impairments in cognition, mood, and energy regulation—argues against a model of widespread, gross neurodegeneration. A more compelling hypothesis, which forms the basis of this report, is that the symptoms of neurological PASC arise from a chronic state of glial cell dysfunction that impairs the integrity and efficiency of otherwise intact neural circuits. This shifts the primary investigative focus from neuronal death to the sustained failure of the brain's essential glial support network.

1.2. Central Mechanisms of CNS Injury: Beyond Direct Viral Neuroinvasion

The mechanisms underlying the neurological manifestations of PASC are multifaceted and complex. While initial investigations explored the possibility of direct viral neurotropism and widespread infection of the brain parenchyma, a consensus is emerging that this is a relatively rare event.16 Although SARS-CoV-2 RNA has been detected in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and in post-mortem brain tissue of some patients, the viral load is typically low, and evidence of active, productive replication within neurons is limited.16 This suggests that the profound and lasting neurological symptoms are not primarily caused by direct viral-mediated destruction of brain cells.

Instead, the dominant paradigm points toward indirect mechanisms of CNS injury, driven largely by the host's systemic and local inflammatory response to the virus.3 The primary drivers of neuropathology are now understood to include sustained neuroinflammation, microvascular injury, endothelial dysfunction, disruption of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), and potential autoimmune phenomena.4 This model posits that the initial infection, even if confined to the respiratory tract, can trigger a cascade of events that culminates in a chronic, self-perpetuating inflammatory state within the CNS. A key component of this hypothesis is the potential for persistence of viral components, particularly the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, in the CNS or in CNS-adjacent tissues. Even in the absence of whole, replicating virions, these viral remnants can act as a persistent source of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), continually stimulating resident immune cells of the brain and driving chronic inflammation.27 Therefore, the central pathology of neurological PASC appears to be less about the virus itself being in the brain and more about the brain's protracted and dysfunctional reaction to the virus having been in the body.

1.3. The Role of Viral Persistence, Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption, and Systemic Inflammation

The transition from an acute viral illness to a chronic neurological condition is underpinned by three interconnected processes: viral persistence, BBB disruption, and systemic inflammation.

Viral Persistence: Mounting evidence indicates that SARS-CoV-2 or its components can remain in the body long after the acute infection has resolved. Viral RNA and proteins have been detected in various tissues, including the gastrointestinal tract, heart, and brain, for months or even years post-infection.21 Of particular relevance to neuropathology, recent studies have identified significant accumulation of the spike protein in the meninges (the protective layers surrounding the brain) and the skull's bone marrow, where it can persist for extended periods.30 These sites, which are in close proximity to the CNS, may act as reservoirs, providing a sustained source of PAMPs that fuel chronic inflammation at the brain's borders.30

Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption: The systemic hyperinflammation characteristic of acute COVID-19, often termed a "cytokine storm" involving elevated levels of interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), inflicts significant damage on the vascular endothelium, including the highly specialized endothelium of the BBB.17 This leads to a breakdown in the integrity of the BBB, increasing its permeability.6 A compromised BBB allows for the infiltration of peripheral immune cells, circulating cytokines, and other neurotoxic molecules from the bloodstream into the brain parenchyma, a process that both initiates and perpetuates a neuroinflammatory state.32 The activation of perivascular cells, such as astrocytes and pericytes, is a key step in mediating this vascular dysfunction and subsequent immune infiltration.13

Autoimmunity: SARS-CoV-2 infection can also disrupt immune tolerance, leading to the generation of autoantibodies.23 These autoantibodies may target neuronal, glial, or vascular proteins, initiating an autoimmune attack on the CNS.11 This immune-mediated process can contribute directly to neuronal damage and demyelination, adding another layer of complexity to the post-infectious neuropathology.21 Together, these three mechanisms create a vicious cycle: persistent viral antigens fuel systemic inflammation, which damages the BBB, allowing inflammatory mediators to enter the brain, where they activate resident glial cells and may contribute to a localized autoimmune response, leading to the chronic neuroinflammation that underlies the symptoms of neurological PASC.

Section 2: Microglia: Sentinels Turned Instigators of Chronic Neuroinflammation

2.1. Transcriptomic and Proteomic Signatures of Long-Term Microglial Activation

Microglia, as the resident myeloid-lineage immune cells of the CNS, are primary responders to pathological insults and play a central role in orchestrating the neuroinflammatory response in PASC.7 A key initiating event is the direct activation of microglia by the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, which functions as a PAMP. This interaction is mediated through pattern recognition receptors, most notably Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), triggering a downstream signaling cascade that shifts microglia from a homeostatic, surveying state to a reactive, pro-inflammatory phenotype.27 This activation occurs irrespective of direct viral replication within the brain, indicating that the mere presence of viral proteins is sufficient to initiate a robust microglial response.28

This phenotypic shift is substantiated by multi-omic analyses of post-mortem brain tissue from COVID-19 patients and animal models. Transcriptomic profiling consistently reveals a significant upregulation of gene pathways associated with inflammation, immune responses, and cytokine signaling.18 This molecular signature points directly to microglia-driven neuroinflammation as a core pathogenic mechanism underlying the neuronal and behavioral abnormalities observed post-infection.36 The activation leads to the production and release of a potent cocktail of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including the characteristic triad of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α.27 These mediators, which are found to be persistently elevated in individuals with Long COVID, are known to disrupt synaptic function, impair neurogenesis, and contribute to the overall toxic microenvironment that damages other neural cell types.25 Post-mortem analysis confirms intense microgliosis, particularly in white matter regions, providing histological evidence for this sustained state of activation.18

2.2. Functional Consequences: From Synaptic Pruning to Impaired Neuronal Homeostasis

The long-term consequences of chronic microglial activation extend beyond the secretion of inflammatory molecules to a profound disruption of their essential homeostatic functions, most critically the regulation of synaptic architecture. In a healthy state, microglia play a vital role in sculpting neural circuits by selectively pruning unnecessary or weak synapses. However, in the reactive state induced by SARS-CoV-2, this process becomes dysregulated and pathological. Activated microglia engage in excessive phagocytosis, leading to the inappropriate removal of functional synapses and a net loss of synaptic density.7

This microglia-dependent engulfment of synapses has been directly demonstrated in mouse models, providing a powerful mechanistic link between the viral spike protein, microglial activation, and the cognitive deficits characteristic of "brain fog".25 The complement cascade, a key pathway of the innate immune system, is a critical mediator of this pathological pruning. Pro-inflammatory astrocytes, themselves activated during the neuroinflammatory response, release complement component C3. This C3 protein fragments, and its product, C3b, opsonizes or "tags" synapses, marking them for elimination by microglia, which express the complement receptor 3 (CR3).43 This creates a deleterious crosstalk pathway between astrocytes and microglia that converges on synaptic destruction, particularly in vulnerable regions like the hippocampus.43 The resulting loss of synaptic connections directly undermines the structural basis of learning and memory, offering a compelling cellular explanation for the persistent cognitive impairments reported by Long COVID patients.

2.3. Dysregulation of Purinergic and Inflammasome Signaling Pathways

The sustained pro-inflammatory state of microglia in PASC is maintained through the dysregulation of specific intracellular signaling pathways, particularly the purinergic and inflammasome systems. Purinergic signaling is a primary mechanism by which microglia sense cellular damage, responding to extracellular nucleotides like ATP and ADP that are released by stressed or injured cells.36 Exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein fundamentally alters this sensory apparatus, inducing the upregulation of multiple purinergic receptor transcripts and proteins, including P2X7 and P2Y12.28 This change does not merely activate the microglia; it rewires their signaling machinery to be hyper-reactive to subsequent danger signals.

The upregulation of the P2X7 receptor is particularly consequential. P2X7 is an ion channel that, upon binding ATP, triggers a potent inflammatory cascade. Its activation is a critical upstream event for the assembly and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, a multi-protein complex within the microglia.25 The activated NLRP3 inflammasome, in turn, cleaves pro-IL-1β into its mature, highly inflammatory form, which is then secreted from the cell.25 This P2X7-NLRP3-IL-1β axis constitutes a powerful feed-forward loop, where initial inflammation leads to increased sensitivity (via P2X7 upregulation), which then amplifies the subsequent inflammatory response (via NLRP3 and IL-1β), locking the microglia into a chronic, easily triggered state of activation. This molecular mechanism helps to explain the persistent and often relapsing-remitting nature of neurological symptoms in PASC, as even low levels of ongoing cellular stress within the CNS could be sufficient to provoke an exaggerated and damaging microglial response.

Section 3: Astrocytic Dysfunction: A Collapse of Neuronal Support Systems

3.1. Astrocytes as a Viral Target: Infection, Replication, and Reactive Astrogliosis

In the landscape of the CNS, astrocytes emerge as a cell type with a particular vulnerability to SARS-CoV-2. A substantial body of evidence derived from post-mortem analysis of human brain tissue, advanced in vitro models such as human cortical organoids, and primary cell cultures converges on the finding that astrocytes are a preferential target for direct viral infection and replication.6 This tropism appears to be mediated primarily by the co-receptor Neuropilin-1 (NRP1), as astrocytes express very low levels of the canonical viral receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2).6

The consequence of this infection is a profound cellular transformation into a state of reactive astrogliosis. This is not a passive response but an active, pathological remodeling of the cell's structure and function. At the molecular level, transcriptomic analysis of infected astrocytes reveals the significant upregulation of canonical astrogliosis markers, including SERPINA3 (alpha-1 antichymotrypsin), CD44, and S100A10.47 This genetic reprogramming is accompanied by morphological changes and a shift toward a pro-inflammatory phenotype, where the astrocytes themselves become a source of inflammatory mediators, contributing to and amplifying the overall neuroinflammatory environment initiated by microglia.6 This transformation effectively converts astrocytes from essential guardians of neuronal homeostasis into active participants in the neuropathological process.

3.2. Metabolic Reprogramming and its Impact on the Astrocyte-Neuron Lactate Shuttle

One of the most detrimental consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection in astrocytes is a severe disruption of their central metabolic functions. Astrocytes are the primary energy managers of the brain, and their metabolic coupling with neurons is essential for proper brain function. Unbiased proteomic and metabolomic profiling of infected astrocytes has uncovered a dramatic and extensive remodeling of cellular metabolism, with pathways related to carbon and glucose utilization being among the most significantly affected.6

Specifically, infected astrocytes exhibit a pathological increase in their own glucose consumption and respiration.48 However, this is coupled with a paradoxical and sharp decrease in the intracellular levels of pyruvate and lactate.48 These molecules are the end products of glycolysis and are the primary substrates for the astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle (ANLS), a fundamental process whereby astrocytes export these energy-rich molecules to fuel neuronal activity. The infection effectively causes astrocytes to hoard these energy resources for their own heightened metabolic state, thereby starving adjacent neurons. Furthermore, the infection leads to a reduction in astrocytic glutamine and its derivatives, glutamate and GABA.48 Astrocytes are responsible for the glutamate-glutamine cycle, which clears excess glutamate from the synapse and provides neurons with the precursor glutamine for synthesizing new neurotransmitters. The disruption of this cycle compromises both excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission. This dual metabolic failure—the collapse of both the energy supply chain and the neurotransmitter precursor supply chain—severely impairs neuronal function and resilience.

3.3. The Secretory Phenotype of Infected Astrocytes and Non-Autonomous Neuronal Injury

Beyond the passive damage caused by the withdrawal of metabolic support, infected astrocytes actively contribute to neuronal injury through the adoption of a toxic secretory phenotype. Experiments using conditioned media from SARS-CoV-2-infected astrocyte cultures have demonstrated that these cells release soluble factors that are directly harmful to neurons, significantly reducing neuronal viability and increasing rates of apoptosis.48 This form of "non-autonomous" cell death is critical because it occurs in the absence of direct neuronal infection; the damage is mediated entirely by the toxic products secreted by the nearby infected astrocytes.48

This finding provides a powerful explanatory mechanism for how localized pockets of astrocyte infection can lead to widespread neuronal dysfunction and contribute to the structural brain changes, such as the reductions in cerebral cortical thickness, that have been observed in COVID-19 patients, even those with mild initial symptoms.46 The pathological remodeling of astrocytes also involves the downregulation of key transporters, such as the glutamate transporter GLT-1, which is responsible for clearing excess glutamate from the synaptic cleft.56 Impaired glutamate uptake can lead to its accumulation in the extracellular space, resulting in excitotoxicity—a process where excessive stimulation of glutamate receptors leads to neuronal damage and death.56 Thus, the infected astrocyte orchestrates a multi-pronged assault on neuronal health: it simultaneously fuels neuroinflammation, withholds essential metabolic and neurotransmitter support, and secretes directly neurotoxic factors, creating a profoundly hostile microenvironment that drives the neuropathology of Long COVID.

Section 4: Oligodendrocyte and Myelin Integrity: Collateral Damage of a Pro-Inflammatory Milieu

4.1. Evidence for Demyelination and Oligodendrocyte Depletion in Post-COVID Neuropathology

The chronic neuroinflammatory state established by reactive microglia and astrocytes has significant downstream consequences for the white matter of the brain, specifically impacting oligodendrocytes and the integrity of the myelin sheaths they produce. A compelling body of evidence from multiple research modalities points to demyelination and white matter pathology as a core feature of neurological PASC.8 Animal models employing mild respiratory SARS-CoV-2 infection, where the virus is confined to the lungs, have been instrumental in demonstrating this link. These studies reveal a significant and persistent depletion of both mature, myelinating oligodendrocytes and their progenitor cells (OPCs) in subcortical white matter regions, which is accompanied by a quantifiable loss of myelinated axons.7

These preclinical findings are increasingly corroborated by studies in human patients. Post-mortem histological analyses of brain tissue from individuals who died with COVID-19 have revealed areas of myelin loss and axonal injury.61 Furthermore, advanced neuroimaging techniques applied to Long COVID survivors provide in vivo evidence of white matter alterations. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technique that measures the directional diffusion of water molecules, has shown changes in metrics such as mean diffusivity (MD) and radial diffusivity (RD) in the white matter of PASC patients. Increases in RD, in particular, are considered a sensitive marker for demyelination.66 More direct methods, such as quantitative myelin water imaging, which estimates the amount of water trapped within the myelin sheath, are also being employed to specifically assess myelin content and have the potential to provide more definitive evidence of demyelination in this population.69

4.2. Mechanisms of Myelin Damage: The Interplay of Cytokines, Microglial Reactivity, and Hypoxia

The prevailing evidence suggests that oligodendrocytes are not a primary target of direct SARS-CoV-2 infection. Rather, the damage they sustain is largely a secondary consequence of the toxic and inflamed microenvironment created by other glial cells—a clear case of "bystander" or "collateral" damage.7 Several mechanisms contribute to this oligodendrocyte pathology.

First, the pro-inflammatory cytokines that are hallmarks of the PASC neuroinflammatory state, particularly TNF-α and IL-6 released by reactive microglia and astrocytes, are known to be directly toxic to oligodendrocytes. These cytokines can induce apoptosis in mature oligodendrocytes and inhibit the differentiation and maturation of OPCs, thereby halting the production of new myelin.38 Second, reactive microglia, in their chronically activated state, directly impair the homeostasis of the oligodendrocyte lineage. Beyond cytokine release, their altered phagocytic activity and loss of supportive functions create an environment that is hostile to the survival and function of both OPCs and mature oligodendrocytes.7 Third, in cases of more severe acute COVID-19, systemic factors such as hypoxia and microvascular thrombosis can lead to ischemic injury in the white matter. Oligodendrocytes have a very high metabolic rate and are exceptionally vulnerable to oxygen and glucose deprivation, making white matter particularly susceptible to this form of damage.59

4.3. Impaired Remyelination and the Functional Deficits in Neural Circuitry

The pathology extends beyond the destruction of existing myelin; it also involves a critical failure of the brain's endogenous repair mechanisms. The neuroinflammatory environment not only kills mature oligodendrocytes but also depletes the population of OPCs, the stem-like cells responsible for generating new oligodendrocytes to repair myelin damage (a process known as remyelination).62 This dual insult—the active destruction of myelin combined with the suppression of the machinery for its repair—leads to a net, persistent loss of myelin integrity.74

The functional consequences of this sustained white matter pathology are profound. Myelin is essential for the rapid and efficient propagation of electrical impulses along axons, a process known as saltatory conduction.74 Demyelination slows this conduction velocity and disrupts the precise timing of signal transmission within and between neural circuits.74 This degradation of signal fidelity provides a direct and compelling biological substrate for many of the cognitive symptoms of "brain fog," such as slowed information processing speed, impaired attention, and difficulty with concentration.25 The failure of the brain's resilience mechanisms to overcome the inflammatory assault and repair the resulting damage is a key factor in the chronicity of these neurological deficits.

Section 5: The Epigenetic Scars of Infection: Sustaining Glial Dysfunction in Long COVID

5.1. Principles of Epigenetic Regulation in the CNS: DNA Methylation and Histone Modification

To understand how an acute viral infection can lead to a chronic neurological disease, it is essential to consider mechanisms that can induce stable, long-term changes in cellular function. Epigenetics, which refers to heritable modifications to DNA and its associated proteins that alter gene expression without changing the underlying DNA sequence, provides such a mechanism.80 The two most well-characterized epigenetic mechanisms are DNA methylation and post-translational modifications of histone proteins. DNA methylation typically involves the addition of a methyl group to cytosine bases, primarily at CpG dinucleotides. Generally, methylation in gene promoter regions is associated with transcriptional repression, effectively silencing gene expression.81 Histone modifications are a more complex "code" of chemical marks—such as acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation—added to the tails of histone proteins around which DNA is wrapped. These marks alter chromatin structure, making genes more (euchromatin) or less (heterochromatin) accessible to the transcriptional machinery.81 Crucially, these epigenetic patterns are not static; they are dynamic and can be written, erased, and read by specific enzymes in response to environmental stimuli, including inflammation and viral infection, leading to lasting shifts in a cell's identity and behavior.80

5.2. "Trained Immunity" in Microglia: An Epigenetic Memory of Inflammation

The central hypothesis to explain the sustained activation of microglia in PASC is the concept of "trained immunity." This phenomenon, first described in peripheral innate immune cells, refers to a form of immunological memory mediated by epigenetic reprogramming.85 Following an initial stimulus (the "training"), innate immune cells undergo stable epigenetic changes that leave them in a heightened state of alert, enabling a faster and more robust response to a secondary, unrelated stimulus.87

Compelling evidence for this process in the context of COVID-19 comes from studies of peripheral monocytes in survivors of severe infection. These studies have revealed persistent epigenetic alterations, such as increased chromatin accessibility at the promoters of inflammatory genes, that last for up to a year after the acute illness.85 These epigenetic marks are believed to be established in long-lived hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) and are then passed down to their short-lived monocyte progeny, ensuring the persistence of the "trained" phenotype.87 The inflammatory cytokine IL-6, a hallmark of severe COVID-19, has been identified as a critical factor in imprinting this epigenetic memory.87

This model provides a powerful framework for understanding chronic microglial activation. As the long-lived, self-renewing immune cells of the CNS, microglia are ideal candidates for retaining such an epigenetic memory.91 It is hypothesized that the acute neuroinflammatory event associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection acts as the "training" stimulus, establishing durable histone modifications—such as the activating marks H3K27 acetylation (H3K27ac) and H3K4 trimethylation (H3K4me3)—at the loci of key inflammatory genes.88 This epigenetic reprogramming lowers the activation threshold of the microglia, locking them into a hyper-responsive, pro-inflammatory state that persists long after the initial viral trigger has subsided.

5.3. Evidence for Altered DNA Methylation in Astrocytes and Other CNS-Relevant Cells

While direct evidence of epigenetic changes within the glial cells of Long COVID patients remains an area of active investigation, a growing number of studies provide strong circumstantial support for this mechanism. In vitro experiments have utilized DNA methylation sequencing to characterize the changes in host gene expression that occur in astrocytes following direct SARS-CoV-2 infection, establishing that the virus can indeed alter the astrocyte epigenome.50

Furthermore, studies analyzing peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from individuals with Long COVID have identified distinct, long-lasting DNA methylation signatures when compared to individuals who fully recovered or were never infected.29 These differentially methylated regions are often located in genes critical for immune regulation, metabolic function, and redox balance.83 For example, one study found an inverse correlation between the expression of the pro-inflammatory chemokine CCL11—a molecule linked to cognitive impairment in PASC—and the methylation levels of specific CpG sites in its promoter region.108 This provides a direct link between an epigenetic mark, the expression of a key neuroinflammatory mediator, and a clinical outcome. While these findings are in peripheral cells, they establish the principle that SARS-CoV-2 infection leaves a lasting epigenetic footprint and strongly suggest that similar processes are occurring within the long-lived glial cell populations of the CNS.109

5.4. A Unifying Hypothesis: How Epigenetic Reprogramming "Locks In" a Pathological Glial State

Synthesizing these lines of evidence leads to a unifying model where epigenetic reprogramming serves as the crucial bridge between an acute viral infection and a chronic neurological disease. The initial, intense neuroinflammatory response to SARS-CoV-2 (whether from peripheral cytokine influx or direct CNS cell activation) acts as an epigenetic "writer." This event establishes a new set of durable epigenetic marks—including permissive histone acetylation at inflammatory gene promoters in microglia and potentially aberrant DNA methylation patterns in astrocytes—that fundamentally alter the cells' transcriptional landscape.52

These epigenetic modifications are not easily erased and effectively "lock in" a dysfunctional, pro-inflammatory gene expression program. For microglia, this manifests as a state of trained immunity, characterized by hyper-reactivity and a propensity for pathological phagocytosis. For astrocytes, it may sustain a state of reactive astrogliosis with impaired metabolic and neuro-supportive functions. This epigenetically maintained pathological state persists long after the initial viral stimulus has been cleared, providing a robust molecular explanation for the chronicity of neurological PASC and the failure of the CNS to return to homeostasis.104 This transforms the conceptualization of Long COVID from a condition of simple, non-resolving inflammation to one of maladaptive, epigenetically learned inflammation.

Section 6: Synthesis and Therapeutic Horizons

6.1. An Integrated Model of Glial Crosstalk in Long COVID Neuropathology

The long-term neurological consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection can be understood as a pathological cascade rooted in the dysfunction and maladaptive crosstalk of the brain's glial cell populations. This integrated model synthesizes the cell-specific alterations into a coherent sequence of events that explains the persistence of symptoms.

Initiation: The process begins with an initial inflammatory trigger. This can be the influx of systemic cytokines and immune cells across a compromised BBB or the direct activation of CNS cells by persistent viral components, such as the spike protein, in the brain or its surrounding tissues. This initial insult serves as an epigenetic "training" event for microglia, the CNS's primary immune responders. Through mechanisms like histone modification, microglia are epigenetically reprogrammed, locking them into a chronic state of heightened reactivity and a pro-inflammatory posture.

Amplification: These "trained" microglia become the central drivers of a self-perpetuating neuroinflammatory cycle. They persistently release a cocktail of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-1β. These signals, in turn, induce a state of reactive astrogliosis in neighboring astrocytes. This astrocytic response is amplified if the astrocytes are also directly infected by SARS-CoV-2, which further skews their function toward a pathological state. A key element of this amplification loop is the crosstalk between the two cell types: reactive astrocytes release complement proteins (e.g., C3) that tag synapses for destruction, a process executed by the hyper-phagocytic, complement-receptor-expressing microglia.

Execution: The combined toxic microenvironment created by the chronically activated microglia and dysfunctional astrocytes leads to the execution of neuronal and white matter damage. Neurons suffer from a multi-pronged assault: they are starved of metabolic support due to the collapse of the astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle, their synaptic connections are pathologically pruned by microglia, and they are exposed to a neurotoxic and potentially excitotoxic milieu. Concurrently, oligodendrocytes, which are highly vulnerable to inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress, undergo apoptosis. This leads to demyelination, and the same inflammatory environment suppresses the function of oligodendrocyte precursor cells, crippling the brain's capacity for myelin repair.

The ultimate outcome is a widespread disruption of neural circuit function. The loss of synapses impairs the basis of learning and memory, while the loss of myelin slows the speed and disrupts the timing of information processing. This functional disruption, rather than large-scale neuronal death, manifests clinically as the cognitive slowing, memory problems, and attentional deficits that constitute "brain fog," as well as the chronic fatigue and mood disturbances characteristic of neurological PASC.

6.2. Gaps in Current Knowledge and Future Research Imperatives

While significant progress has been made, several critical gaps in our understanding of neurological PASC remain. Addressing these will be essential for developing effective diagnostics and treatments.

Human CNS Studies: The majority of the mechanistic data, particularly regarding epigenetics, comes from animal models or peripheral human cells. There is an urgent need for direct analysis of epigenetic marks (genome-wide DNA methylation and histone modification profiles) in specific, sorted glial cell populations from well-characterized post-mortem brain tissue of Long COVID donors.31 This is the most direct way to validate the "trained immunity" hypothesis in human microglia.

Longitudinal Cohort Studies: Cross-sectional studies have been invaluable, but longitudinal research is required to map the trajectory of neuropathology. Such studies should integrate advanced, quantitative neuroimaging (e.g., PET ligands for microglial activation, myelin water imaging) with serial analysis of CSF and plasma for biomarkers of neuroinflammation, axonal injury, and glial activation.66 This will help to understand how the pathology evolves over time and to identify individuals at highest risk for long-term decline.

Advanced Preclinical Models: While current animal models have been informative, there is a need to develop models that more accurately recapitulate the chronic, low-grade, and persistent nature of the neuroinflammatory state in PASC. This includes models of viral persistence and models that allow for the detailed mechanistic dissection of the complex crosstalk between different glial cell types.

Defining Causality: The precise contribution of different initial triggers (e.g., severity of acute disease, specific viral variant, host genetics, viral persistence vs. transient inflammation) to the establishment of the chronic glial pathology needs to be delineated.

6.3. Potential Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Glial Activation and Epigenetic Pathways

The current management of neurological PASC is largely symptomatic and rehabilitative, focusing on cognitive therapy and managing symptoms like fatigue and pain.11 However, the detailed mechanistic understanding of glial dysfunction opens the door to novel, targeted therapeutic strategies.

Targeting Microglial Activation: Given their central role, microglia are a prime therapeutic target. Potential strategies include the use of small molecule inhibitors that target key signaling nodes, such as P2X7 receptor antagonists or NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors, to dampen their hyper-reactive state. Modulating microglial metabolism could also shift them from a pro-inflammatory to a more homeostatic phenotype.

Restoring Astrocyte Function: Therapies aimed at restoring the normal homeostatic and neuro-supportive functions of astrocytes could be beneficial. This might include metabolic modulators designed to correct the deficits in the lactate shuttle or compounds that promote glutamate uptake to reduce excitotoxicity.

Promoting Remyelination: To address the white matter damage, strategies that promote the survival and differentiation of OPCs are needed. A number of such compounds are in development for other demyelinating diseases like multiple sclerosis and could be repurposed for PASC if the underlying pathology is confirmed.

Epigenetic and Immunomodulatory Therapies: The most novel and potentially transformative approach would be to target the underlying epigenetic memory. The use of "epidrugs," such as histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors or DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) inhibitors, could potentially "reset" the maladaptive epigenetic landscape in glial cells, restoring a more normal gene expression program. Similarly, therapies that target the upstream drivers of this reprogramming, such as IL-6 receptor blockade (as suggested by peripheral cell studies), could prevent the establishment of this chronic state if administered early.

In conclusion, a comprehensive understanding of the long-term impact of SARS-CoV-2 on the brain's glial cells reveals a complex interplay of inflammation, metabolic disruption, and failed repair, all likely sustained by durable epigenetic changes. Future research focused on dissecting these pathways and developing therapies to restore glial homeostasis holds the promise of alleviating the significant and lasting neurological burden of Long COVID.

Acknowledgement

I acknowledge the use of Gemini AI in the preparation of this report. Specifically, it was used to: (1) brainstorm and refine the initial research questions; (2) assist in writing and debugging Python scripts for statistical analysis; and (3) help draft, paraphrase, and proofread sections of the final manuscript. I reviewed, edited, and assume full responsibility for all content.

Works cited

Long-term neurological and cognitive impact of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis in over 4 million patients - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12166599/

Long-term neurological sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection - PubMed, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36192556/

Long-term neurological dysfunction associated with COVID-19: Lessons from influenza and inflammatory diseases? - PubMed, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38014645/

Neurological sequelae of long COVID: a comprehensive review of diagnostic imaging, underlying mechanisms, and potential therapeutics - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11881597/

Central Nervous System Manifestations of Long COVID: A Systematic Review - PubMed, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40453253/

Proteomic changes in SARS-CoV-2-infected human astrocytes and... - ResearchGate, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Proteomic-changes-in-SARS-CoV-2-infected-human-astrocytes-and-postmortem-brain-tissue_fig4_362639099

The neurobiology of long COVID - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9537254/

(PDF) Mild respiratory SARS-CoV-2 infection can cause multi ..., accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357760291_Mild_respiratory_SARS-CoV-2_infection_can_cause_multi-lineage_cellular_dysregulation_and_myelin_loss_in_the_brain

Long-Term Effects of SARS-CoV-2 in the Brain: Clinical Consequences and Molecular Mechanisms - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10179128/

Neurological sequelae of long COVID: a comprehensive review of diagnostic imaging, underlying mechanisms, and potential therapeutics - Frontiers, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neurology/articles/10.3389/fneur.2024.1465787/full

(PDF) Understanding Post-COVID-19: Mechanisms, Neurological Complications, Current Treatments, and Emerging Therapies - ResearchGate, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/387143378_Understanding_Post-COVID-19_Mechanisms_Neurological_Complications_Current_Treatments_and_Emerging_Therapies

Mechanisms, Effects, and Management of Neurological Complications of Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (NC-PASC) - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9953707/

Unraveling the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein long-term effect on neuro-PASC - Frontiers, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cellular-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fncel.2024.1481963/full

Post-COVID cognitive dysfunction: current status and research recommendations for high risk population - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10344681/

Long COVID Is Associated with Severe Cognitive Limitations Among U.S. Adults - MDPI, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2673-8112/5/4/46

Neuroproteomic Analysis after SARS-CoV-2 Infection Reveals Overrepresented Neurodegeneration Pathways and Disrupted Metabolic Pathways - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10669333/

Network medicine links SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 infection to brain microvascular injury and neuroinflammation in dementia-like cognitive impairment - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8010732/

Brain-wide alterations revealed by spatial transcriptomics and proteomics in COVID-19 infection | Request PDF - ResearchGate, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/385816130_Brain-wide_alterations_revealed_by_spatial_transcriptomics_and_proteomics_in_COVID-19_infection

Next-Generation Sequencing and Proteomics of Cerebrospinal Fluid From COVID-19 Patients With Neurological Manifestations - Frontiers, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.782731/full

SARS-CoV-2 causes brain inflammation via impaired neuro-immune interactions - bioRxiv, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.07.13.499991.full

The pathogenesis of neurologic symptoms of the post-acute ..., accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9179102/

Unraveling the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein long-term effect on neuro-PASC - DOAJ, accessed August 31, 2025, https://doaj.org/article/39f811e41c4f44c4ae6ce0224b9a532b

Pathogenic mechanisms of post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) - eLife, accessed August 31, 2025, https://elifesciences.org/articles/86002

Vascular Dysfunctions Contribute to the Long-Term Cognitive Deficits Following COVID-19, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2079-7737/12/8/1106

Cognitive Dysfunction in Long COVID - Encyclopedia.pub, accessed August 31, 2025, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/58394

The Molecular Mechanisms of Cognitive Dysfunction in Long COVID: A Narrative Review - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12154490/

Role of SARS-CoV-2 Spike-Protein-Induced Activation of Microglia and Mast Cells in the Pathogenesis of Neuro-COVID - MDPI, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4409/12/5/688

SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein alters microglial purinergic signaling - Frontiers, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1158460/full

Long COVID: Molecular Mechanisms and Detection Techniques - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10778767/

Long COVID: SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Accumulation Linked to Long-Lasting Brain Effects, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.helmholtz-munich.de/en/newsroom/news-all/artikel/long-covid-sars-cov-2-spike-protein-accumulation-linked-to-long-lasting-brain-effects

RECOVER's tissue pathology (autopsy) study makes unique contributions to Long COVID research, accessed August 31, 2025, https://recovercovid.org/news/recovers-tissue-pathology-autopsy-study-makes-unique-contributions-long-covid-research

Neuropathobiology of COVID-19: The Role for Glia - Frontiers, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cellular-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fncel.2020.592214/full

Long COVID and its association with neurodegenerative diseases: pathogenesis, neuroimaging, and treatment - Frontiers, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neurology/articles/10.3389/fneur.2024.1367974/full

Long COVID and its Effects on the Central Nervous System - Global Autoimmune Institute, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.autoimmuneinstitute.org/covid_timeline/long-covid-and-its-effects-on-the-central-nervous-system/

The Influence of Microglia on Neuroplasticity and Long-Term Cognitive Sequelae in Long COVID: Impacts on Brain Development and Beyond - MDPI, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/25/7/3819

SARS-CoV-2 neurotropism-induced anxiety/depression-like ..., accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.10.02.560570v2.full

A review of cytokine-based pathophysiology of Long COVID symptoms - Frontiers, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/medicine/articles/10.3389/fmed.2023.1011936/full

Linking brain inflammation to long-COVID and other neurological conditions, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pls.llnl.gov/article/52661/linking-brain-inflammation-long-covid-other-neurological-conditions

New insights on the role of microglia in synaptic pruning in health and disease., accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.broadinstitute.org/publications/broad144186

Long Covid brain fog: a neuroinflammation phenomenon? - Oxford Academic, accessed August 31, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/ooim/article/3/1/iqac007/6722625

The Influence of Microglia on Neuroplasticity and Long-Term Cognitive Sequelae in Long COVID: Impacts on Brain Development and Beyond - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11011312/

The Influence of Microglia on Neuroplasticity and Long-Term Cognitive Sequelae in Long COVID: Impacts on Brain Development and Beyond - ResearchGate, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/379407103_The_Influence_of_Microglia_on_Neuroplasticity_and_Long-Term_Cognitive_Sequelae_in_Long_COVID_Impacts_on_Brain_Development_and_Beyond

Astrocyte-derived complement C3 facilitated microglial phagocytosis of synapses in Staphylococcus aureus-associated neurocognitive deficits | PLOS Pathogens - Research journals, accessed August 31, 2025, https://journals.plos.org/plospathogens/article?id=10.1371/journal.ppat.1013126

COVID, complement, and the brain - Frontiers, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1216457/full

Heterogeneous complement and microglia activation mediates stress-induced synapse loss, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.06.28.546889v2.full-text

SARS-CoV-2 infects brain astrocytes of COVID-19 patients and impairs neuronal viability, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/projects/PXD023781

SARS-CoV2 infection triggers inflammatory conditions and ..., accessed August 31, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/stmcls/article/43/6/sxaf010/8086416

(PDF) SARS-CoV-2 infects brain astrocytes of COVID-19 patients ..., accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346879020_SARS-CoV-2_infects_brain_astrocytes_of_COVID-19_patients_and_impairs_neuronal_viability

Study reveals main target of SARS-CoV-2 in brain and describes effects of virus on nervous system - Agência FAPESP, accessed August 31, 2025, https://agencia.fapesp.br/study-reveals-main-target-of-sars-cov-2-in-brain-and-describes-effects-of-virus-on-nervous-system/39669

NEUROPILIN-1 MEDIATES SARS-COV-2 INFECTION OF ASTROCYTES PROMOTING NEURON DYSFUNCTION A B A B D C A B - CROI Conference, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.croiconference.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/posters/2022/CROI2022_Poster_171.pdf

Neuropilin-1 Mediates SARS-CoV-2 Infection of Astrocytes in Brain Organoids, Inducing Inflammation Leading to Dysfunction and Death of Neurons - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9765283/

Histone acetylation in astrocytes is microglia-dependent. (A)... - ResearchGate, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Histone-acetylation-in-astrocytes-is-microglia-dependent-A-Astrocyte-enriched-cultures_fig4_352564483

Astrocytes and the Psychiatric Sequelae of COVID-19: What We Learned from the Pandemic - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9362636/

SARS-CoV-2 infects brain astrocytes of COVID-19 patients and impairs neuronal viability, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.10.09.20207464v3.full-text

SARS-CoV-2 infects brain astrocytes of COVID-19 patients and impairs neuronal viability, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.10.09.20207464v4.full-text

Glutamate Excitotoxicity Is Involved in the Induction of Paralysis in Mice after Infection by a Human Coronavirus with a Single Point Mutation in Its Spike Protein - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3209392/

Glutamate Excitotoxicity Is Involved in the Induction of Paralysis in Mice after Infection by a Human Coronavirus with a Single Point Mutation in Its Spike Protein - ASM Journals, accessed August 31, 2025, https://journals.asm.org/doi/abs/10.1128/jvi.05576-11

Glial activation and excitotoxicity following COVID-19 illness - ResearchGate, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Glial-activation-and-excitotoxicity-following-COVID-19-illness-In-glutamatergic_fig3_359926886

Role of Demyelination in the Persistence of Neurological and Mental Impairments after COVID-19 - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9569975/

COVID-19-associated CNS Demyelinating Diseases - Jefferson Digital Commons, accessed August 31, 2025, https://jdc.jefferson.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1048&context=department_neuroscience

Neuropathology of COVID-19: a spectrum of vascular and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM)-like pathology - ScienceOpen, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.scienceopen.com/document_file/54ea1d79-6749-4def-8750-576edda87b06/PubMedCentral/54ea1d79-6749-4def-8750-576edda87b06.pdf

Even mild SARS-CoV-2 respiratory-only infection can cause long-term neurologic damage, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.news-medical.net/news/20220116/Even-mild-SARS-CoV-2-respiratory-only-infection-can-cause-long-term-neurologic-damage.aspx

(PDF) Role of Microglia, Decreased Neurogenesis and Oligodendrocyte Depletion in Long COVID-Mediated Brain Impairments - ResearchGate, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/374187932_Role_of_Microglia_Decreased_Neurogenesis_and_Oligodendrocyte_Depletion_in_Long_COVID-Mediated_Brain_Impairments

Role of Microglia, Decreased Neurogenesis and Oligodendrocyte Depletion in Long COVID-Mediated Brain Impairments - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10676788/

Role of Microglia, Decreased Neurogenesis and Oligodendrocyte Depletion in Long COVID-Mediated Brain Impairments - PubMed, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37815903/

(PDF) Advanced magnetic resonance neuroimaging techniques: Feasibility and applications in long or post-COVID-19 syndrome - A review - ResearchGate, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/378102457_Advanced_magnetic_resonance_neuroimaging_techniques_Feasibility_and_applications_in_long_or_post-COVID-19_syndrome_-_A_review

Advanced magnetic resonance neuroimaging techniques: feasibility and applications in long or post-COVID-19 syndrome - a review - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10923379/

Advanced MRI detects brain changes after Covid-19 - healthcare-in-europe.com, accessed August 31, 2025, https://healthcare-in-europe.com/en/news/advanced-mri-detect-brain-change-after-covid19.html

In vivo multi-slice mapping of myelin water content using T2* decay - ResearchGate, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/43181393_In_vivo_multi-slice_mapping_of_myelin_water_content_using_T2_decay

Myelin Water Fraction - UBC MRI Research Centre - The University of British Columbia, accessed August 31, 2025, https://mriresearch.med.ubc.ca/news-projects/myelin-water-fraction/

Quantitative myelin water imaging using short TR adiabatic inversion recovery prepared echo-planar imaging (STAIR-EPI) sequence - Frontiers, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/radiology/articles/10.3389/fradi.2023.1263491/full

Long COVID, the Brain, Nerves, and Cognitive Function - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10366776/

Oligodendrocytes that survive acute coronavirus infection induce prolonged inflammatory responses in the CNS | PNAS, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2003432117

Myelin - Wikipedia, accessed August 31, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myelin

Flexible Players within the Sheaths: The Intrinsically Disordered Proteins of Myelin in Health and Disease - MDPI, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4409/9/2/470

Reflective imaging of myelin integrity in the human and mouse central nervous systems, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cellular-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fncel.2024.1408182/full

White matter integrity in mice requires continuous myelin synthesis at the inner tongue - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8897471/

Imaging and Quantification of Myelin Integrity After Injury With Spectral Confocal Reflectance Microscopy - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6877500/

Neuronal activity disrupts myelinated axon integrity in the absence of NKCC1b, accessed August 31, 2025, https://rupress.org/jcb/article/219/7/e201909022/151733/Neuronal-activity-disrupts-myelinated-axon

Epigenetic Alterations in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Mechanisms, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Implications - MDPI, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8247/18/9/1281

An Overview of the Epigenetic Modifications in the Brain under Normal and Pathological Conditions - MDPI, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/25/7/3881

Epigenetic Regulation of Inflammatory Signaling and Inflammation-Induced Cancer, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cell-and-developmental-biology/articles/10.3389/fcell.2022.931493/full

Identifying DNA Methylation Patterns in Post COVID-19 Condition: Insights from a One-Year Prospective Cohort Study | medRxiv, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.02.28.25323075v1.full-text

Genetic and Epigenetic Intersections in COVID-19-Associated Cardiovascular Disease: Emerging Insights and Future Directions - MDPI, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9059/13/2/485

COVID-19 and trained immunity: the inflammatory burden ... - Frontiers, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1294959/full

Trained Immunity and Epigenetic Reprogramming in Microglia: A Novel Axis in Alzheimer's Disease Neuroinflammation - IJFMR, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.ijfmr.com/research-paper.php?id=52474

COVID-19 and trained immunity: the inflammatory burden of long covid - PMC, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10713746/

Microglial immune regulation by epigenetic reprogramming through histone H3K27 acetylation in neuroinflammation - Frontiers, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1052925/full

Trained Immunity and Epigenetic Reprogramming in Microglia: A Novel Axis in Alzheimer's Disease Neuroinflammation - ResearchGate, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/394116834_Trained_Immunity_and_Epigenetic_Reprogramming_in_Microglia_A_Novel_Axis_in_Alzheimer's_Disease_Neuroinflammation

Microglial immune regulation by epigenetic reprogramming through histone H3K27 acetylation in neuroinflammation - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10073546/

Epigenetic regulation of innate immune memory in microglia - bioRxiv, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.05.30.446351v1.full-text

Severe COVID-19 can alter long-term immune response - Cornell Chronicle, accessed August 31, 2025, https://news.cornell.edu/stories/2023/08/severe-covid-19-can-alter-long-term-immune-response

Epigenetic memory of coronavirus infection in innate immune cells and their progenitors, accessed August 31, 2025, https://recovercovid.org/publications/epigenetic-memory-coronavirus-infection-innate-immune-cells-and-their-progenitors

Over but not gone: Lingering epigenetic effects of COVID-19 - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10543559/

Microglial Implications in SARS-CoV-2 Infection and COVID-19: Lessons From Viral RNA Neurotropism and Possible Relevance to Parkinson's Disease - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8240959/

Neuropathobiology of COVID-19: The Role for Glia - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7693550/

Microglial immune regulation by epigenetic reprogramming through histone H3K27 acetylation in neuroinflammation - ResearchGate, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369918154_Microglial_immune_regulation_by_epigenetic_reprogramming_through_histone_H3K27_acetylation_in_neuroinflammation

Persistent epigenetic memory of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in monocyte-derived macrophages | Molecular Systems Biology - EMBO Press, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.embopress.org/doi/10.1038/s44320-025-00093-6

| Histone modifications occurring upon microglia polarization. (A)... | Download Scientific Diagram - ResearchGate, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Histone-modifications-occurring-upon-microglia-polarization-A-Post-translational_fig1_326808454

DNA methylation changes during acute COVID-19 are associated with long-term transcriptional dysregulation in patients' airway epithelial cells - EMBO Press, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.embopress.org/doi/10.1038/s44321-025-00215-5

New Study Identifies Profile of Long Covid in Blood DNA - Albany Med Health System, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.albanymed.org/news/study-identifies-profile-of-long-covid/

Differential DNA methylation 7 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection - PubMed, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40251596/

Mild SARS-CoV-2 infection modifies DNA methylation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from COVID-19 convalescents | medRxiv, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.07.05.21260014v1

DNA methylation in long COVID - Frontiers, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/virology/articles/10.3389/fviro.2024.1371683/full

View of Epigenetic markers as predictors of neurodegeneration in long COVID survivors, accessed August 31, 2025, https://jcbior.com/index.php/JCBioR/article/view/315/586

Epigenetic changes in patients with post-acute COVID-19 symptoms (PACS) and long-COVID: A systematic review, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11505605/

The Initial COVID-19 Reliable Interactive DNA Methylation Markers and Biological Implications - MDPI, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2079-7737/13/4/245

Vitamin B12 as an epidrug for regulating peripheral blood biomarkers in long COVID-associated visuoconstructive deficit - PMC, accessed August 31, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11923054/

DNA methylation changes in glial cells of the normal-appearing white matter in Multiple Sclerosis patients - medRxiv, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.06.21.21258936v1.full.pdf

DNA methylation changes in glial cells of the normal-appearing white matter in Multiple Sclerosis patients | medRxiv, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.06.21.21258936v1

Epigenetic Regulation of Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's Disease - MDPI, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4409/13/1/79

Chromatin Landscape Defined by Repressive Histone Methylation during Oligodendrocyte Differentiation | Journal of Neuroscience, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.jneurosci.org/content/35/1/352

The epigenetic landscape of oligodendrocyte progenitors changes with time - bioRxiv, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2024.02.06.579145v1.full-text

Epigenetic Lens to Visualize the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) Infection in COVID-19 Pandemic - Frontiers, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/genetics/articles/10.3389/fgene.2021.581726/full

Characterizing Oligodendrocyte-Lineage Cells and Myelination in the Basolateral Amygdala: Insights from a Novel Methodology in Postmortem Human Brain | bioRxiv, accessed August 31, 2025, https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.01.09.631560v1

COVID-BRAIN Project: Neuroimaging in long COVID, accessed August 31, 2025,

https://covidbrainstudy.umn.edu/