Accelerated Immunosenescence Following SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Comprehensive Analysis of T-Cell Repertoire, Telomere Dynamics, and Long-Term Clinical Sequelae

SARS-CoV-2 accelerates immune aging, shrinking T-cell diversity and telomeres, raising risks for Long COVID, infections, and cancer.

Section 1: The Convergence of Aging, Inflammation, and Viral Pathogenesis

The global COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has served as an unprecedented clinical and scientific stress test, revealing profound vulnerabilities within the human population. Chief among these is the stark age gradient in disease severity, a phenomenon that points not merely to the passage of time but to the fundamental biological processes of aging itself. SARS-CoV-2 does not infect individuals in a vacuum; it encounters a host immune system that has been shaped and remodeled by a lifetime of exposures and intrinsic aging processes. This section establishes the critical immunological context in which SARS-CoV-2 operates, detailing the concepts of immunosenescence and inflammaging. It posits that these age-related phenomena are not just comorbidities but the primary physiopathological substrate that dictates the severity of COVID-19. Furthermore, it introduces the "immunobiography" framework—the unique history of an individual's immune challenges—as an essential lens through which to understand the heterogeneous outcomes of infection, framing SARS-CoV-2 as a potent new entry that both exploits and exacerbates the aging of the immune system.

1.1 The Landscape of Immunosenescence and Inflammaging

The gradual deterioration of immune function with advancing age, a process termed immunosenescence, is a central feature of human aging.1 It is not a simple collapse of the immune system but rather a complex and dynamic remodeling of both its innate and adaptive arms, resulting in a state of diminished responsiveness to new threats and impaired regulation of existing responses.2 This multifactorial process is characterized by a reduced capacity to respond to novel antigens, a contraction of the diverse repertoire of immune receptors, and a paradoxical expansion of memory T-cells that can contribute to a pro-inflammatory state.3

At the heart of immunosenescence lies the aging of the T-cell compartment. The thymus, the primary lymphoid organ responsible for generating new, naïve T-cells, undergoes a progressive process of atrophy known as thymic involution, which begins in early life and accelerates after puberty.4 This decline in thymopoiesis severely curtails the output of naïve T-cells, which are essential for recognizing and mounting an effective response against novel pathogens.5 As the pool of naïve T-cells shrinks, the immune system becomes increasingly reliant on the homeostatic proliferation of existing memory T-cells to fill the "immunological space".6 This leads to a skewed T-cell repertoire, dominated by clones specific to previously encountered antigens, and a diminished ability to effectively counter new infectious challenges like SARS-CoV-2.5

Intricately linked to immunosenescence is the phenomenon of "inflammaging," a term coined to describe the chronic, low-grade, systemic pro-inflammatory state that characterizes the elderly.1 This persistent inflammatory milieu is not driven by acute infection but by the lifelong accumulation of endogenous inflammatory triggers, including cellular damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and the accumulation of senescent cells.1 Senescent cells, which have entered a state of irreversible growth arrest, secrete a complex mixture of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and proteases known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP).7 Tissue macrophages, in particular, are key contributors to inflammaging, and their own age-related functional decline further fuels this pro-inflammatory environment.1

Immunosenescence and inflammaging exist in a vicious, self-perpetuating cycle. A senescent immune system is less capable of resolving inflammation and clearing senescent cells, thereby allowing the drivers of inflammaging to persist and accumulate.8 In turn, the chronic inflammatory environment of inflammaging actively promotes the senescence and functional exhaustion of immune cells, further degrading the quality of the immune response.2 This creates a state where the aged immune system is both less effective at fighting pathogens and simultaneously predisposed to hyper-inflammation, a dangerous combination when confronted with a novel virus.

1.2 The Pre-Conditioned Host: Immunosenescence as a Primary Risk Factor for Severe COVID-19

The epidemiological data from the COVID-19 pandemic are unequivocal: advanced chronological age is the single greatest non-modifiable risk factor for severe disease, hospitalization, and death.1 The statistics are stark, with studies showing that, compared to young adults (ages 18–29), the risk of death from COVID-19 is approximately 140 times higher in those aged 75–84 and an astonishing 8,700 times higher in individuals 85 years and older.10 While comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic lung disease are also significant risk factors, age remains the dominant predictor of adverse outcomes.10

This strong epidemiological correlation is not coincidental; it reflects a deep mechanistic link where immunosenescence and inflammaging serve as the key physiopathological substrates that predispose the elderly to a dysregulated and ineffective immune response against SARS-CoV-2.4 The aged immune system is, in essence, pre-conditioned for the catastrophic hyperinflammation that defines severe COVID-19. Healthy elderly individuals often exhibit high baseline levels of circulating pro-inflammatory biomarkers such as C-reactive protein, Interleukin-6 (IL-6), and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α)—a profile that mirrors the "cytokine storm" observed in critically ill COVID-19 patients.5 When SARS-CoV-2 infects an older individual, it encounters a host whose immune cells, particularly monocytes and macrophages, are already "primed" and poised to generate a massive and polyfunctional pro-inflammatory cytokine release upon stimulation.1 This explains why the immune response in the elderly is often not weak, but rather excessive and damaging.

This vulnerability is compounded by age-related defects in the initial, innate immune response. Alveolar macrophages in the aged lung exhibit reduced phagocytic capacity and a diminished ability to control lung damage during viral infection.1 Furthermore, the interferon (IFN) response, a critical first line of antiviral defense, is often blunted in senescent cells, allowing for more efficient viral replication in the early stages of infection.1 Paradoxically, age-related changes in the virus's own receptor can also contribute to pathology. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), the primary cellular receptor for SARS-CoV-2, has anti-inflammatory properties. Studies have shown that ACE2 expression is reduced in the lungs of aged animals and elderly humans.10 While this might suggest fewer entry points for the virus, the downregulation of ACE2 by viral entry can exacerbate a pro-inflammatory state by allowing levels of its substrate, the pro-inflammatory mediator Angiotensin II, to rise unchecked, further contributing to the cytokine storm and acute lung injury.10 The host's pre-existing state of immunosenescence, therefore, creates a permissive environment for both viral replication and subsequent immunopathology.

1.3 The Concept of Immunobiography

While chronological age is a powerful population-level predictor, it fails to capture the significant heterogeneity in COVID-19 outcomes observed among individuals of the same age.1 This variability is explained by the concept of "immunobiography," which posits that the state of an individual's immune system is the product of their unique, cumulative history of immunological challenges throughout life.8 This personal history—encompassing all prior infections, vaccinations, environmental exposures, and even encounters with transformed cells—shapes the trajectory of immune aging, meaning that an individual's "immunological age" may differ substantially from their chronological age.8 A "richer" immunobiography, laden with more frequent or chronic inflammatory challenges, can accelerate the onset and progression of immunosenescence and inflammaging, adversely affecting reactivity to a novel pathogen like SARS-CoV-2 even in young or middle-aged individuals.8

Chronic infection with Cytomegalovirus (CMV), a ubiquitous herpesvirus, serves as a paradigmatic example of an immunobiographical factor that accelerates immune aging. Although typically asymptomatic in healthy individuals, latent CMV infection establishes a lifelong persistence that places a significant and continuous burden on the immune system.15 To maintain control over the virus, the immune system must dedicate a substantial fraction of its T-cell resources, leading to the massive expansion of CMV-specific memory T-cells, often occupying a large portion of the T-cell compartment in the elderly.16 This chronic stimulation drives the accumulation of late-differentiated, senescent T-cell phenotypes, contributes to systemic inflammation, and constricts the naïve T-cell pool, thereby shaping the overall immune landscape.15 Consequently, CMV seropositivity is strongly associated with many of the hallmarks of immunosenescence and may be a key factor affecting the quality of the T-cell response to SARS-CoV-2.17

Within this framework, SARS-CoV-2 infection must be viewed not only as an event influenced by the host's prior immunobiography but as a profound and lasting new entry into that biography. The infection itself affects the function of both the innate and adaptive branches of the immune system, leaving a durable imprint.8 The subsequent development of post-acute sequelae, or Long COVID, characterized by chronic inflammation and autoimmune phenomena, suggests that the virus can induce a prolonged, deleterious remodeling of the immune system.8 This viral encounter has the potential to significantly accelerate an individual's trajectory toward a state of manifest immunosenescence and inflammaging, potentially hastening the onset of other age-related diseases and increasing vulnerability to future health threats.8 The true impact of COVID-19, therefore, extends far beyond the acute illness, permanently altering the immunological landscape of the host.

This reframes the entire understanding of risk. The data collectively suggest that COVID-19 severity is less a function of chronological age itself and more a function of biological age, specifically the biological age of the immune system. The concepts of inflammaging and immunobiography are the mechanistic links that explain why some younger individuals with a "richer" immunobiography—for example, those with chronic CMV infection or multiple prior inflammatory insults—experience severe disease, while some chronologically older individuals fare better. This shifts risk stratification from a simple demographic metric to a more complex immunological one. Future public health strategies may need to consider biomarkers of immune aging for more precise risk assessment. Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 acts as an "accelerant" on the pre-existing fire of inflammaging. An aged individual's immune system is already smoldering with low-grade inflammation.5 SARS-CoV-2 does not merely add fuel; its interaction with senescent cells and dysregulated innate responses acts like an accelerant, causing the smoldering fire to erupt into a destructive cytokine storm.1 This explains the non-linear, explosive nature of disease progression in vulnerable hosts, as a feed-forward loop is established: pre-existing inflammation leads to a disproportionate response to the virus, which in turn drives more inflammation and cellular senescence. This is not an additive effect, but a synergistic explosion that accounts for the rapid clinical deterioration observed in severe cases.

Section 2: SARS-CoV-2-Induced Remodeling of the T-Cell Compartment

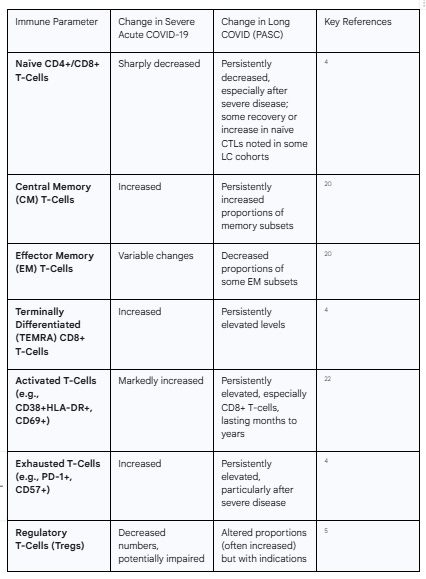

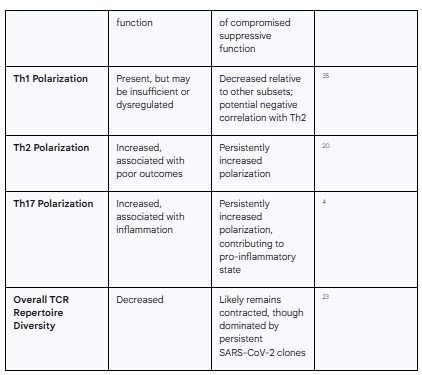

The encounter between SARS-CoV-2 and the human immune system, particularly in cases of severe disease, leaves a profound and lasting imprint on the adaptive immune landscape. The T-cell compartment, central to the control of viral infections and the establishment of long-term immunity, undergoes a significant and measurable remodeling that bears the hallmarks of accelerated aging. This section directly addresses the question of whether SARS-CoV-2 infection causes a lasting reduction in the diversity of the T-cell repertoire. By synthesizing data from detailed immunophenotyping and high-throughput T-cell receptor (TCR) sequencing studies, a clear picture emerges of post-COVID T-cell dysregulation, characterized by the contraction of the naïve T-cell pool, the accumulation of senescent and exhausted T-cells, and a state of persistent immune activation that is particularly prominent in individuals with Long COVID.

2.1 Contraction of the Naïve T-Cell Pool and Repertoire Diversity

A cardinal feature of immunosenescence is the age-related decline in the production and peripheral maintenance of naïve T-cells, which are critical for responding to novel antigens.6 Compelling evidence from multiple longitudinal studies demonstrates that severe COVID-19 infection dramatically accelerates this process. In survivors of severe disease, a significant and persistent reduction in both the frequency and absolute numbers of naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells is observed months after the initial infection.4 This acute depletion of the naïve T-cell pool, a cornerstone of a versatile adaptive immune system, represents a significant step towards an aged immune phenotype.6

The loss of naïve T-cells has direct consequences for the diversity of the T-cell receptor (TCR) repertoire, which represents the immune system's collective capacity to recognize a vast array of potential pathogens. High-throughput sequencing analyses have revealed a discernible decrease in the diversity of TCR clonotypes in the peripheral blood of COVID-19 patients when compared to healthy controls.23 This contraction of the repertoire is not uniform; its magnitude correlates directly with the severity of the disease, with critically ill patients showing a less diverse TCR repertoire than those with non-critical illness.23

While the overall diversity of the T-cell repertoire diminishes, the infection simultaneously drives a massive and highly focused clonal expansion of T-cells that are specific to SARS-CoV-2 antigens. This results in a re-shaping of the immunological landscape, where a few dominant, virus-specific T-cell clones expand to occupy a much larger proportion of the T-cell compartment.23 In individuals who develop Long COVID, these prominent SARS-CoV-2-specific T-cell pools are remarkably stable and can be maintained for at least two years following the initial infection.26 This creates a complex immunological picture: the overall repertoire becomes less diverse and more restricted, while the virus-specific repertoire is robust, deep, and extraordinarily long-lasting. Longitudinal analyses confirm that a detectable T-cell signal against the virus persists in the vast majority of individuals for at least 15 months post-infection, and the magnitude of the initial T-cell response is predictive of this lasting signal.27 This reveals a critical trade-off: the immune system mounts a powerful and durable memory response to SARS-CoV-2, but potentially at the cost of its breadth and preparedness for future, unrelated pathogens. This state can be described as a form of "immune fixation," where the system becomes hyper-focused on a past threat, sacrificing the plasticity that a diverse naïve T-cell pool provides. This is a more profound alteration than simply becoming "a few years older" immunologically; it is a qualitative reprogramming that may underlie increased susceptibility to other infections following COVID-19.

2.2 The Signature of T-Cell Exhaustion and Senescence

Beyond the changes in naïve and memory populations, the T-cell compartment in convalescents from severe COVID-19 displays a distinct phenotypic shift towards exhaustion and senescence. There is a marked and persistent accumulation of highly differentiated T-cell populations, such as terminally differentiated effector memory RA+ (TEMRA) CD8+ T-cells and senescent T-cells expressing markers like CD57 and lacking the critical co-stimulatory molecule CD28 ($CD28^{-}$$CD57^{+}$).4 These cell types are characteristic of an aged immune system and possess limited proliferative capacity and altered effector functions.

A key molecular signature of this process is the sustained upregulation of immune checkpoint molecules, or "exhaustion markers," such as Programmed Cell Death protein 1 (PD-1) and T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 (TIM-3).26 In survivors of severe COVID-19, both the frequency and absolute numbers of PD-1-expressing exhausted CD8+ T-cells are significantly elevated months after recovery.4 In individuals with Long COVID, SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T-cells have been shown to preferentially express exhaustion markers like PD-1 and CTLA4 at 8 months post-infection, although some studies suggest these specific markers may not persist out to 24 months.26 This state of T-cell exhaustion is indicative of chronic antigen stimulation and functional impairment, a hallmark of the immune system's inability to fully clear a pathogen.

This phenotypic evidence is corroborated at the molecular level by transcriptomic analyses of immune cells from convalescent patients. The transcriptome of individuals who recovered from severe COVID-19 shows a distinct signature of enhanced immune aging, with upregulation of genes associated with exhaustion (e.g., LAG3) and cellular senescence pathways.4 Concurrently, these cells exhibit downregulation of genes involved in crucial maintenance processes like DNA damage repair (e.g., ATM) and autophagy (e.g., Atg7, Atg5). These defects in core cellular housekeeping functions are fundamental processes that underlie and drive immunosenescence, providing strong evidence that the changes observed after severe COVID-19 are not merely transient but reflect a deeper, programmatic shift toward an aged cellular state.4

2.3 Persistent Activation and Skewed Polarization in Long COVID

Post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), or Long COVID, is increasingly understood not as a passive state of prolonged recovery but as an active disease process characterized by persistent and dysregulated immune activation. A consistent finding across multiple studies is the presence of chronically elevated levels of activated T-cells, particularly CD8+ T-cells, that can persist for many months, and in some cases up to two years, after the initial infection.22 This cellular activation is often accompanied by a low-grade inflammatory state, with elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, and various interferons (IFNs).29 The immunological profile of Long COVID is therefore one of an immune system that has failed to return to homeostasis and remains locked in a state of unresolved activation. This persistent activation and exhaustion seen in Long COVID closely mirrors the immunological state observed in chronic viral infections like CMV or untreated HIV, which strongly suggests a common underlying driver: persistent antigen. This observation lends significant weight to the hypothesis that viral reservoirs—lingering SARS-CoV-2 virus or protein fragments in tissues—are a key pathophysiological mechanism of Long COVID. These reservoirs would act as a source of continuous antigenic stimulation, perpetually driving T-cells towards a dysfunctional, exhausted, and senescent state, providing a clear mechanistic rationale for investigating antiviral therapies for this condition.

This chronic activation is further complicated by a dysregulation of key immunoregulatory cell populations. Regulatory T-cells (Tregs), which are essential for suppressing excessive immune responses and maintaining self-tolerance, appear to be perturbed in Long COVID.31 While some studies report an increased proportion of Tregs among the CD4+ T-cell population in PASC patients, there are indications that their suppressive function may be impaired.29 A failure of Treg-mediated control could directly contribute to the persistent inflammation and the emergence of autoimmune phenomena reported in Long COVID.

Furthermore, the balance between different subsets of helper T-cells, which orchestrate the nature of the immune response, is skewed. In both acute severe disease and in the chronic state of Long COVID, there is evidence of a shift away from a protective, antiviral Th1-dominant response towards a more pro-inflammatory and potentially pathogenic Th2 and Th17 polarization.4 This Th2/Th17 bias is hypothesized to be a key driver of autoimmune mechanisms in Long COVID, potentially triggered by molecular mimicry or a general loss of immune tolerance in a chronically inflamed environment.20 This specific pattern of immune imbalance—weakened regulatory control from Tregs combined with a bias towards inflammatory helper T-cells—provides a direct mechanistic bridge to the increased risk of post-viral autoimmune conditions. It is a textbook recipe for the loss of self-tolerance, explaining the clinical emergence of autoimmune-like symptoms and the detection of autoantibodies in a subset of patients following COVID-19.

The following table summarizes the key alterations in T-cell populations, comparing the changes observed during severe acute COVID-19 with the persistent dysregulation characteristic of Long COVID.

Section 3: Telomere Dynamics as a Biomarker of Accelerated Immune Aging

Beyond the phenotypic and functional reprogramming of the T-cell compartment, SARS-CoV-2 infection leaves a more fundamental scar on immune cells: the premature erosion of telomeres. Telomeres, the repetitive nucleotide sequences that cap the ends of chromosomes, serve as a biological clock, shortening with each round of cell division. Their length is a robust and quantifiable biomarker of cellular aging. This section directly addresses the second major component of the inquiry, evaluating the evidence that SARS-CoV-2 infection causes a measurable and lasting shortening of telomeres in immune cells. By synthesizing data from cross-sectional studies, longitudinal analyses, and meta-analyses, a strong case emerges linking the virus to accelerated telomere attrition, providing a molecular correlate for the concept of infection-induced immunosenescence.

3.1 The Mechanistic Link Between Viral Infection and Telomere Attrition

The accelerated shortening of telomeres in immune cells during and after a viral infection is driven by two primary, interconnected mechanisms: replicative senescence and inflammation-induced oxidative stress.

First, mounting an effective adaptive immune response to a novel pathogen like SARS-CoV-2 requires the massive and rapid proliferation of antigen-specific lymphocytes. A single naïve T-cell, upon recognizing its cognate viral antigen, can undergo numerous rounds of division to generate a large army of effector cells capable of clearing the virus.38 This process of clonal expansion imposes a significant "replicative stress" on the lymphocyte population. Due to the "end-replication problem," whereby DNA polymerase cannot fully replicate the very ends of linear chromosomes, a small segment of telomeric DNA is lost with each cell division.38 The intense proliferative burst needed to combat SARS-CoV-2 thus consumes a substantial portion of the replicative lifespan of responding immune cells, leading to a marked acceleration of telomere shortening.39

Second, the impact of the virus extends beyond replicative demands. Severe COVID-19 is characterized by a state of intense systemic inflammation and profound oxidative stress, driven by the cytokine storm and the activation of innate immune cells.40 Telomeric DNA, with its guanine-rich repeat sequence, is particularly susceptible to damage from reactive oxygen species (ROS).42 This oxidative damage can cause single-strand breaks and other lesions within the telomeres, leading to their degradation and shortening through mechanisms that are independent of cell division.40 Therefore, the hyperinflammatory environment of severe COVID-19 directly attacks the structural integrity of telomeres, compounding the shortening caused by cellular replication and further hastening the journey toward cellular senescence.

3.2 Evidence for Premature Telomere Shortening in COVID-19

A substantial body of evidence now confirms that SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with significant telomere attrition in peripheral blood leukocytes. A systematic review and meta-analysis incorporating data from 1,604 participants provided a robust conclusion: individuals who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 display significantly shorter telomere lengths compared to uninfected control subjects.43 This finding establishes a clear link between infection status and this key biomarker of cellular aging.

Crucially, the degree of telomere shortening is not uniform across all patients but correlates strongly with the severity of the acute illness. Multiple independent studies have demonstrated that patients who experience severe or critical COVID-19 have significantly shorter telomeres than those with moderate or mild forms of the disease.43 This dose-dependent relationship suggests that the immunological and inflammatory burden of the infection is a primary driver of telomere erosion. Survivors of severe COVID-19 are thus left with an immune system that is, by this molecular measure, biologically older than before the infection.

This accelerated aging is not a transient effect that resolves upon viral clearance. Longitudinal studies indicate that the telomere shortening persists long after the acute phase of the disease. Individuals who have recovered from SARS-CoV-2 have been found to have shorter telomeres even a year after their initial infection, with the degree of shortening again associated with the severity of their original illness.49 This phenomenon is also linked to the development of Long COVID. The condition known as persistent post-COVID-19 syndrome (PPCS) has been associated with significant telomere shortening, suggesting that the ongoing processes driving Long COVID symptoms may also contribute to sustained cellular aging.40 In a paradoxical and intriguing finding, one smaller study of Long COVID patients reported an increase in leukocyte telomere length and reactivated telomerase activity.50 While this contrasts with the bulk of the evidence, it raises the possibility of complex, dysregulated cellular repair mechanisms or even aberrant cellular activity in a subset of patients, a finding that warrants significant further investigation due to its potential implications for conditions like cancer.

3.3 Telomere Length as a Prognostic and Susceptibility Factor

The relationship between telomere length and COVID-19 is bidirectional. Just as infection can shorten telomeres, pre-existing telomere length appears to be a powerful prognostic factor for disease outcomes. Individuals who enter the infection with already short telomeres—a reflection of advanced chronological or biological age, or a history of chronic inflammation—are at a significantly higher risk of developing severe COVID-19.39 Independent of chronological age and sex, longer leukocyte telomere length is associated with more favorable clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients, including a lower odds ratio for ICU admission and the need for mechanical ventilation.40 In this sense, telomere length serves as a marker of an individual's "immunological reserve" or resilience—their capacity to withstand the profound stress of a novel viral infection. Individuals with short T-cell telomeres tend to mount a weak T-cell response and an inadequately suppressed, hyperactive innate immune response, leading to the cytokine storm and severe lung injury.45

However, the question of causality is complex and nuanced. While the strong association in observational studies is clear, a Mendelian randomization study—a genetic epidemiology method used to infer causality—did not find evidence to support genetically predicted shorter telomere length as a direct causal risk factor for COVID-19 susceptibility or severity.54 This apparent contradiction is critical to understanding the role of telomeres. It suggests that while an individual's inherited predisposition for telomere length may not be a primary driver of risk, their acquired telomere length at the moment of infection is a powerful indicator of their underlying biological state. Telomere length is influenced not just by genetics, but by a lifetime of exposures—stress, lifestyle, and prior infections, i.e., their immunobiography.39 The Mendelian randomization study isolates the genetic component and finds it is not causal. Therefore, the risk observed in clinical studies must be associated with the acquired telomere shortening that reflects this cumulative history. This resolves the conflict by positioning telomeres not as a simple cause of vulnerability, but as a crucial integrative biomarker. They are a molecular readout that summarizes the accumulated damage, inflammation, and senescence that truly confers risk. This provides a quantifiable, molecular-level validation of the "biological age" hypothesis. SARS-CoV-2 infection effectively imposes a "biological age tax" on the immune system, measurable in the currency of telomere base pairs, with the amount of tax paid being proportional to the severity of the infection. This transforms the concept of accelerated aging from a metaphor into a measurable biological event.

Section 4: Clinical Sequelae of Post-SARS-CoV-2 Immunosenescence

The accelerated immunosenescence induced by SARS-CoV-2, as evidenced by the remodeling of the T-cell compartment and the attrition of telomeres, is not merely a set of abstract laboratory findings. These profound alterations to the immune system have tangible, long-term clinical consequences, directly addressing the question of whether the infection leaves individuals more vulnerable to subsequent health threats. The dysregulated and aged immune state following COVID-19 creates a permissive environment for a spectrum of pathologies, ranging from an increased susceptibility to opportunistic infections to a heightened risk of cancer development and progression. This section synthesizes the evidence for these clinical sequelae, illustrating how the immunological scars of COVID-19 can manifest as future disease.

4.1 Increased Vulnerability to Opportunistic Pathogens

One of the most immediate consequences of an aged and dysfunctional immune system is an impaired ability to control other pathogens. A systematic review and meta-analysis has quantified this risk, finding a pooled prevalence of opportunistic, secondary, or superinfections in COVID-19 patients of approximately 16%.55 This risk is substantially higher in critically ill patients, who are most likely to suffer from the severe immune dysregulation, including lymphopenia, that characterizes severe COVID-19.55

The spectrum of opportunistic infections is broad, reflecting the widespread nature of the immune defects. Bacterial superinfections are common, with pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Escherichia coli frequently isolated, particularly in the context of hospital-acquired pneumonia.55 Invasive fungal diseases have emerged as a particularly devastating complication. Conditions such as COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA), invasive candidiasis, and mucormycosis (the so-called "black fungus") are associated with high mortality rates, especially in patients with comorbidities like diabetes or those receiving immunosuppressive therapies such as corticosteroids.57 The risk is not limited to bacteria and fungi; parasitic infections, including the reactivation of latent Toxoplasma gondii and hyperinfection with Strongyloides stercoralis, have also been increasingly reported in COVID-19 patients.56

A critical aspect of this increased vulnerability is the reactivation of latent viruses, a classic consequence of waning T-cell surveillance. The functional exhaustion and depletion of CD8+ T-cells create an opportunity for persistent herpesviruses to escape immune control. Reactivation of Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV), Cytomegalovirus (CMV), and Human Herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) has been documented during and after COVID-19.62 This viral reactivation is not only an indicator of immune incompetence but is also proposed as a potential mechanistic driver of Long COVID symptoms, contributing to the state of chronic inflammation and fatigue by adding to the body's total antigenic burden.62

This vulnerability is further exacerbated by the profound disruption of the gut-lung axis. SARS-CoV-2 infection is known to cause significant gut microbiome dysbiosis, characterized by a loss of beneficial, short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing bacteria and an overgrowth of pro-inflammatory pathobionts.64 This imbalance compromises the integrity of the intestinal barrier, leading to increased permeability or "leaky gut".70 Consequently, bacterial products like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and even whole bacteria can translocate from the gut into the systemic circulation.70 This microbial translocation acts as a powerful, continuous stimulus for systemic inflammation, which in turn can worsen lung pathology and create a systemic environment that is more susceptible to opportunistic pathogens.56 The post-COVID immune landscape thus creates a "perfect storm" for both opportunistic infections and, as discussed next, cancer. These are not independent risks but are mechanistically linked. The same T-cell exhaustion that allows EBV to reactivate is what prevents effective tumor surveillance. The same chronic inflammation, fueled by gut dysbiosis and senescent cells, that promotes tumorigenesis also creates a vulnerable state for secondary bacterial or fungal invasion. This implies a unified clinical risk profile, suggesting that patients presenting with one post-COVID complication, such as shingles (VZV reactivation), should be considered at higher risk for others, a critical consideration for long-term clinical surveillance.

4.2 The Nexus of Chronic Inflammation and Carcinogenesis

The link between chronic inflammation and cancer is well-established, and the persistent, low-grade inflammatory state characteristic of both inflammaging and Long COVID provides a fertile ground for carcinogenesis. The immune dysregulation following SARS-CoV-2 infection could plausibly increase long-term cancer risk through several distinct, yet overlapping, molecular pathways.

First and foremost is the profound impairment of immune surveillance. The exhaustion, senescence, and depletion of cytotoxic CD8+ T-cells and Natural Killer (NK) cells, as detailed in Section 2, fundamentally compromise the immune system's ability to perform one of its most critical functions: identifying and eliminating nascent malignant cells before they can establish themselves as tumors.75 An immune system that is chronically activated, exhausted, and fixated on a past viral threat is an ineffective guardian against new oncogenic threats.

Second, the pro-tumorigenic inflammatory environment itself actively drives cancer development. The elevated levels of cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α, which are hallmarks of both severe COVID-19 and Long COVID, are known to promote cancer cell proliferation, survival, angiogenesis (the formation of new blood vessels to feed a tumor), and metastasis.76 This chronic inflammatory milieu creates a microenvironment that is highly conducive to tumor growth and progression.

Third, there is emerging evidence of direct viral oncogenic mechanisms. Studies have shown that specific SARS-CoV-2 proteins can interact with and promote the degradation of crucial tumor suppressor proteins, including p53 and the retinoblastoma protein (Rb).75 The virus has also been shown to activate well-known oncogenic signaling pathways within host cells, such as the JAK-STAT and NF-κB pathways, which are involved in cell proliferation and survival.75 Finally, the process of virus-induced cellular senescence, while initially a tumor-suppressive mechanism, can become pro-tumorigenic through the SASP, which can remodel the surrounding tissue to support cancer growth.77

4.3 Awakening Dormant Malignancies and Assessing Long-Term Incidence

Perhaps one of the most concerning potential long-term risks is the ability of the intense inflammation triggered by COVID-19 to "awaken" dormant cancer cells. Many cancer patients can remain disease-free for years after treatment, only to suffer a relapse from metastatic disease originating from microscopic clusters of cancer cells that had remained dormant. Preclinical research has produced striking results in this area: in mouse models of breast cancer, respiratory infection with either influenza virus or a coronavirus led to a massive, more than 100-fold expansion of previously dormant cancer cells in the lungs.81 This suggests that the inflammatory storm in the lungs during a severe respiratory infection can provide the necessary signals to jolt these sleeping cancer cells back into active proliferation. Early analyses of human data from the pandemic align with these preclinical findings, showing a higher risk of death from metastatic cancer among cancer survivors who were infected with COVID-19 compared to those who were not.81

Translating these mechanistic risks into population-level evidence is a significant challenge. Analysis of national cancer registry data from the post-pandemic era is complicated by a massive confounding variable: the profound disruption to healthcare services. In 2020, there was a sharp, artificial decline in cancer diagnoses across the board, a direct result of lockdowns, reduced screening, and delayed medical visits.83 In 2021 and 2022, incidence rates for many cancers returned to pre-pandemic levels, but they did not exhibit a compensatory surge that would account for all the diagnoses missed in 2020.85 This indicates a persistent deficit of diagnoses, likely resulting in a cohort of patients who will be diagnosed at later, more advanced stages in the coming years. Notably, some specific cancers, such as metastatic breast cancer, did show higher-than-expected incidence rates in 2021, which could reflect either the consequences of delayed diagnosis or a true biological effect of the virus on disease progression.85 This highlights a critical public health blind spot. The immediate, disruptive effect of the pandemic on healthcare has created a large-scale data artifact that may mask a slower, more subtle, long-term biological effect of the virus on cancer incidence for years, or even decades, to come. The true oncogenic impact of SARS-CoV-2 may not become apparent in population-level registry data for a decade, long after the acute phase of the pandemic has receded. Disentangling these effects will require carefully designed, long-term cohort studies that track infection history and cancer outcomes over time.

Section 5: Future Trajectories: Therapeutic Horizons and Public Health Imperatives

The recognition of SARS-CoV-2 as a potent accelerator of immunosenescence necessitates a paradigm shift in our approach to managing both the acute and long-term consequences of the infection. The focus must expand beyond purely antiviral strategies to include interventions that bolster host resilience and mitigate the downstream effects of immune aging. This concluding section explores emerging therapeutic strategies aimed at counteracting SARS-CoV-2-induced immunosenescence, outlines critical recommendations for the long-term surveillance of at-risk populations, and discusses the broader implications for future pandemic preparedness. The insights gleaned from the COVID-19 pandemic underscore the urgent need to integrate the principles of geroscience—the study of the biology of aging—into infectious disease research and public health policy.

5.1 Novel Therapeutic Strategies

The understanding that cellular senescence and chronic inflammation are key drivers of severe COVID-19 and its long-term sequelae has opened the door to novel therapeutic approaches that target these fundamental aging processes. This represents a significant evolution in infectious disease treatment, moving from a purely "anti-viral" to a "pro-host" or "geroprotective" strategy. Instead of focusing solely on inhibiting the pathogen, these therapies aim to make the aged host less hospitable to the virus and less prone to self-destructive hyperinflammation.

Senolytics: A particularly promising class of drugs is senolytics, which are designed to selectively identify and eliminate senescent cells from the body. Given that senescent cells amplify the inflammatory response to SARS-CoV-2 and contribute to a pro-viral cellular environment, their removal is a logical therapeutic goal.7 Preclinical evidence has been compelling. In aged mice infected with a mouse beta-coronavirus, treatment with senolytic agents—such as Fisetin, or the combination of Dasatinib and Quercetin—dramatically improved outcomes. These therapies reduced mortality rates by up to 50%, lowered systemic and tissue-level inflammatory markers, and enhanced the production of antiviral antibodies.7 These striking results have provided the rationale for initiating clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy of senolytics in treating elderly patients with acute COVID-19 and in alleviating the symptoms of Long COVID.91

Metformin: Another readily available drug that has garnered significant attention is metformin. Primarily used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, metformin possesses well-documented anti-inflammatory and potential anti-aging properties.94 The large-scale COVID-OUT randomized clinical trial, along with subsequent real-world data analyses, has provided strong evidence that early outpatient treatment with metformin during acute SARS-CoV-2 infection can substantially reduce the risk of developing Long COVID. Studies have reported risk reductions ranging from 40% to 64% in overweight or obese adults who initiated treatment shortly after symptom onset.94 While other trials have shown that metformin may not significantly shorten the duration of acute symptoms, its apparent ability to prevent the transition to chronic disease is a major finding.98 The mechanism is thought to involve the drug's ability to mitigate inflammation and potentially interfere with viral replication by modulating cellular energy pathways.95

Other Approaches: The success of these geroprotective strategies points toward a broader range of potential interventions. These include mTOR inhibitors like Rapamycin, which has known anti-aging properties and can block viral replication; dietary interventions or compounds like spermidine that enhance autophagy, a cellular cleaning process that declines with age; and the strategic use of more immunogenic vaccine formulations (e.g., high-dose or adjuvanted vaccines) to overcome the diminished vaccine responsiveness characteristic of an aged immune system.90 This "pro-host" approach is likely not specific to COVID-19 and could represent a new therapeutic platform for protecting the elderly from a wide range of infectious threats, such as influenza and RSV, where immunosenescence is also a key risk factor.

5.2 Recommendations for Long-Term Surveillance

The evidence that SARS-CoV-2 can induce lasting immunological damage and increase the risk for a wide range of chronic diseases necessitates a proactive, long-term approach to the clinical surveillance of survivors. Healthcare systems must prepare for the potential long-tail consequences of the pandemic, which may manifest over years or decades.

A framework for risk stratification is needed to identify individuals who warrant the most intensive monitoring. This high-risk group should include, at a minimum, all survivors of severe or critical COVID-19, older adults, and any individual diagnosed with Long COVID, regardless of the severity of their initial illness. Within this population, heightened clinical vigilance is required in several key areas:

Opportunistic Infections: Clinicians should maintain a low threshold for investigating potential opportunistic infections in post-COVID patients presenting with new or unexplained systemic symptoms. This includes screening for the reactivation of latent viruses like Varicella-Zoster Virus (shingles), EBV, and CMV, which can cause non-specific symptoms such as fatigue and malaise that overlap with Long COVID.

Malignancies: High-risk survivors should be strongly encouraged to adhere to all age- and sex-appropriate cancer screening guidelines. Furthermore, clinicians should be aware of the potential for COVID-19 to accelerate cancer progression or awaken dormant disease. New or persistent symptoms, even if seemingly minor, should be investigated thoroughly to rule out an underlying malignancy.

Autoimmune Disease: Patients should be monitored for the development of new autoimmune phenomena. The onset of symptoms such as persistent joint pain, skin rashes, or unexplained fatigue should prompt an evaluation for autoimmune markers and potential rheumatological disease.

The long-term surveillance needs of the vast number of COVID-19 survivors will place a significant, decades-long burden on healthcare systems that is not currently being adequately planned for. The potential for increased rates of cancer, chronic infections, and autoimmune diseases in tens of millions of people requires an urgent and proactive public health strategy. This must include the development and dissemination of updated clinical guidelines for the long-term care of COVID-19 survivors, comprehensive patient education initiatives to raise awareness of these risks, and dedicated funding for the long-term cohort studies needed to fully quantify the impact of the pandemic on population health.

5.3 Implications for Future Pandemic Preparedness

The COVID-19 pandemic has delivered a stark lesson: the impact of a novel pathogen is determined as much by the biology of the host as it is by the biology of the virus. A population's vulnerability is inextricably linked to its demographic structure and its collective immunological history. This understanding must fundamentally reshape our approach to future pandemic preparedness.

The focus must expand from a strategy centered exclusively on the pathogen—developing vaccines and antivirals after a threat has emerged—to one that also includes strengthening host resilience before the next pandemic arrives. The concept of immunobiography should become a central tenet of public health planning. Strategies must account for the fact that a population's susceptibility is shaped by its age distribution and its cumulative burden of chronic inflammatory states and persistent infections.

This leads to a revolutionary but logical conclusion: the development and strategic deployment of safe, prophylactic "geroscience" or "anti-aging" interventions could become a cornerstone of pandemic preparedness. Proactively treating the underlying drivers of immune aging—such as the accumulation of senescent cells or chronic low-grade inflammation—in high-risk populations could be a powerful way to "immunize" them against the worst outcomes of a future novel pathogen. By making the most vulnerable hosts more resilient, such interventions could flatten the curve of severe disease and death before the next pandemic even begins, effectively decoupling chronological age from immunological vulnerability and creating a more robust and prepared global community.

Acknowledgement

I acknowledge the use of Gemini AI in the preparation of this report. Specifically, it was used to: (1) brainstorm and refine the initial research questions; (2) assist in writing and debugging Python scripts for statistical analysis; and (3) help draft, paraphrase, and proofread sections of the final manuscript. I reviewed, edited, and assume full responsibility for all content.

Works cited

SARS-CoV-2, immunosenescence and inflammaging: partners in ..., accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.aging-us.com/article/103989/text

From aging to long COVID: exploring the convergence of ... - Frontiers, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1298004/full

Humoral and Cellular Immune Responses Against SARS-CoV-2 Following COVID-19 Vaccination in Older Adults: A Systematic Review - ResearchGate, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/394594484_Humoral_and_Cellular_Immune_Responses_Against_SARS-CoV-2_Following_COVID-19_Vaccination_in_Older_Adults_A_Systematic_Review

Accelerated immune ageing is associated with COVID-19 disease ..., accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10782727/

Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): A Perspective from Immunosenescence, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.aginganddisease.org/EN/10.14336/AD.2020.0831

Decreased Naïve T-cell Production Leading to Cytokine Storm as Cause of Increased COVID-19 Severity with Comorbidities - PMC, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7390514/

Senolytics reduce coronavirus-related mortality in old mice - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8607935/

Immunosenescence and COVID-19 - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8975602/

Immunosenescence and ACE2 protein expression: Association with SARS-CoV-2 in older adults, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.organscigroup.us/articles/OJA-6-118.php

SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19 and the Ageing Immune System - PMC, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8570568/

Underlying Conditions and the Higher Risk for Severe COVID-19, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/covid/hcp/clinical-care/underlying-conditions.html

Efficacy and Safety of COVID-19 Vaccination in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis - MDPI, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/11/1/33

The ageing immune system and COVID-19 - British Society for Immunology, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.immunology.org/sites/default/files/2022-09/BSI_Ageing_COVID-19_Report_Nov2020_FINAL.pdf

Immunosenescence and inflamm-ageing in COVID-19 - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9741765/

Cytomegalovirus at the crossroads of immunosenescence and oncogenesis - Open Exploration Publishing, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.explorationpub.com/Journals/ei/Article/100386

CMV and immunosenescence: Open questions. The relevance of the... | Download Scientific Diagram - ResearchGate, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/CMV-and-immunosenescence-Open-questions-The-relevance-of-the-following-questions-on-the_fig1_232745011

Aging and CMV Infection Affect Pre-existing SARS-CoV-2-Reactive CD8+ T Cells in Unexposed Individuals - PubMed Central, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9261342/

Immunosenescence and Cytomegalovirus: Exploring Their Connection in the Context of Aging, Health, and Disease - MDPI, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/25/2/753

Navigating the Post-COVID-19 Immunological Era: Understanding Long COVID-19 and Immune Response - MDPI, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2075-1729/13/11/2121

T Cell Dynamics in COVID-19, Long COVID and Successful Recovery - ResearchGate, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/394060033_T_Cell_Dynamics_in_COVID-19_Long_COVID_and_Successful_Recovery

T Cell Dynamics in COVID-19, Long COVID and Successful Recovery - PMC, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12346483/

Longitudinal Analysis of COVID-19 Patients Shows Age-Associated T Cell Changes Independent of Ongoing Ill-Health - Frontiers, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.676932/full

pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10355153/#:~:text=Results,clones%20increased%20with%20disease%20severity.

T cell receptor β repertoires in patients with COVID-19 reveal disease severity signatures, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10355153/

Leveraging T-cell receptor – epitope recognition models to disentangle unique and cross-reactive T-cell response to SARS-CoV-2 during COVID-19 progression/resolution - Frontiers, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1130876/full

SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T cells from people with long COVID establish and maintain effector phenotype and key TCR signatures over 2 years | PNAS, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2411428121

Longitudinal analysis of T cell receptor repertoires reveals shared ..., accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9220833/

T cell perturbations persist for at least 6 months following hospitalization for COVID-19, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2022.931039/full

Evidence for Long-term Impacts of COVID-19 on Immune Cells and Autoimmune Conditions in Adults – What We Know So, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/Documents/nCoV/COVID-WWKSF/2023/08/long-term-impacts-covid-19-immune-cells-autoimmune-adults.pdf?rev=ee9ec7f21c6e45898a31ca8c9517d089&sc_lang=en

Prolonged T-cell activation and long COVID symptoms independently associate with severe COVID-19 at 3 months - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10319436/

Remodeling of T Cell Dynamics During Long COVID Is Dependent on Severity of SARS-CoV-2 Infection - Frontiers, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2022.886431/full

Regulatory T Cells (Tregs) and COVID-19: Unveiling the Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Potentialities with a Special Focus on Long COVID - PubMed Central, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10059134/

A scoping review of regulatory T cell dynamics in convalescent COVID-19 patients – indications for their potential involvement in the development of Long COVID? - Frontiers, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1070994/full

Profound Immune Dysregulation and Inflammation Found in Long COVID - but no Autoimmunity - Health Rising, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2023/02/27/inflammation-immune-dysregulation-long-covid/

T-Helper Cell Subset Response Is a Determining Factor in COVID-19 Progression, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cellular-and-infection-microbiology/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2021.624483/full

T Cell Dynamics in COVID-19, Long COVID and Successful Recovery - MDPI, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/26/15/7258

Different polarization and functionality of CD4+ T helper subsets in people with post-COVID condition - PubMed Central, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11385313/

COVID-19 mortality and genetic predisposition - Immunopaedia, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.immunopaedia.org.za/breaking-news/covid-19-mortality-and-genetic-predisposition/

Telomere length, epidemiology and pathogenesis of severe COVID ..., accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7435533/

Telomere length and COVID-19 disease severity: insights from hospitalized patients - PMC, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12185540/

The impact of COVID-19 on “biological aging” - Frontiers, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1399676/full

Sex and Age Differences in Telomere Length and Susceptibility to COVID-19, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.jelsciences.com/articles/jbres1159.php

a systematic review and meta-analysis Telomere length in subjects with and without SARS-CoV-2 infection - SciELO, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.scielo.br/j/ramb/a/5rFPyPYBD3PD754xgz8T4Xx/

a systematic review and meta-analysis Telomere length in subjects with and without SARS-CoV-2 infection - SciELO, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.scielo.br/j/ramb/a/5rFPyPYBD3PD754xgz8T4Xx/?lang=en

Correlation between age and COVID-19 severity and telomere length. (A - ResearchGate, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Correlation-between-age-and-COVID-19-severity-and-telomere-length-A-B-Person_fig4_348400242

Association between leukocyte telomere length and COVID-19 severity - PubMed Central, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10225776/

Shorter telomere lengths in patients with severe COVID-19 disease - Aging-US, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.aging-us.com/article/202463/text

Is COVID-19 severity associated with telomere length? A systematic review and meta-analysis - PubMed Central, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10234232/

Comparative Telomere Length in hospitalized COVID-19 patients by... - ResearchGate, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Comparative-Telomere-Length-in-hospitalized-COVID-19-patients-by-persistence-or_fig3_362850115

Leukocyte telomere length and telomerase activity in Long COVID patients from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil - SciELO, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.scielo.br/j/mioc/a/GZHdDNHdVBmcS8yLd89TnmD/

Short telomeres increase the risk of severe COVID-19 - Aging-US, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.aging-us.com/article/104097/text

Shortened Telomere Length is Associated with Adverse Outcomes in COVID-19 Disease, accessed September 11, 2025, https://acquaintpublications.com/article/shortened_telomere_length_is_associated_with_adverse_outcomes_in_covid_19_disease

Telomere length and COVID-19 disease severity: insights from hospitalized patients - Frontiers, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/aging/articles/10.3389/fragi.2025.1577788/full

Telomere Length and COVID-19 Outcomes: A Two-Sample Bidirectional Mendelian Randomization Study - Frontiers, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/genetics/articles/10.3389/fgene.2022.805903/full

(PDF) Opportunistic Infections in COVID-19: A Systematic Review ..., accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359636795_Opportunistic_Infections_in_COVID-19_A_Systematic_Review_and_Meta-Analysis

Potential impact of parasitic opportunistic infections on COVID-19 outcome: A review, accessed September 11, 2025, https://jcmimagescasereports.org/article/JCM-V4-1712.pdf

Post-COVID-19 Fungal Infection in the Aged Population - PMC, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10056493/

An emergence of mucormycosis during the COVID‑19 pandemic (Review), accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.spandidos-publications.com/10.3892/wasj.2024.228

Fungal Diseases and COVID-19, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/hcp/covid-fungal/index.html

Increased Hospitalizations Involving Fungal Infections during COVID-19 Pandemic, United States, January 2020–December 2021 - CDC, accessed September 11, 2025, https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/29/7/22-1771_article

Overview on the Prevalence of Fungal Infections, Immune Response, and Microbiome Role in COVID-19 Patients - MDPI, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2309-608X/7/9/720

Pathophysiological, immunological, and inflammatory features of long COVID - Frontiers, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1341600/full

Persistent SARS-CoV-2 Infection, EBV, HHV-6 and Other Factors May Contribute to Inflammation and Autoimmunity in Long COVID - MDPI, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/15/2/400

The interplay between immune-senescence and inflammaging along with gut... - ResearchGate, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-interplay-between-immune-senescence-and-inflammaging-along-with-gut-microbiome_fig1_355938450

Immunity's core reset: Synbiotics and gut microbiota in the COVID-19 era - PMC, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12304597/

Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in COVID-19: Modulation and Approaches for Prevention and Therapy - MDPI, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/24/15/12249

Mechanisms Leading to Gut Dysbiosis in COVID-19: Current Evidence and Uncertainties Based on Adverse Outcome Pathways - MDPI, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/11/18/5400

SARS-CoV-2 and immune-microbiome interactions: Lessons from respiratory viral infections, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7891052/

Microbiota and COVID-19: Long-term and complex influencing factors - Frontiers, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2022.963488/full

Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis Is a Crucial Player for the Poor Outcomes for COVID-19 in Elderly, Diabetic and Hypertensive Patients - Frontiers, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/medicine/articles/10.3389/fmed.2021.644751/full

Microbiota Modulation of the Gut-Lung Axis in COVID-19 - Frontiers, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.635471/full

Gut microbiota in post-acute COVID-19 syndrome: not the end of the story - Frontiers, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1500890/full

Gut-Lung Axis in COVID-19 - PMC, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7979298/

The Role of the Gut-Lung Axis in COVID-19 Infections and Its Modulation to Improve Clinical Outcomes - IMR Press, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.imrpress.com/journal/FBS/14/3/10.31083/j.fbs1403023/htm

SARS-CoV-2 infection as a potential risk factor for the development ..., accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10518417/

Cancer Occurrence as the Upcoming Complications of COVID-19 ..., accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8831861/

The viral oncogenesis of COVID-19 and its impact on cancer progression, long-term risks, treatment complexities, and research strategies, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.explorationpub.com/Journals/em/Article/1001314

Convergent Mechanisms in Virus-Induced Cancers: A Perspective on Classical Viruses, SARS-CoV-2, and AI-Driven Solutions - PubMed Central, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12027309/

COVID-19 and Carcinogenesis: Exploring the Hidden Links - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11441415/

Correlation of SARS‑CoV‑2 to cancer: Carcinogenic or anticancer? (Review), accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.spandidos-publications.com/10.3892/ijo.2022.5332

CU Cancer Center-led Research Shows That COVID-19 Infection Can Awaken Dormant Cancer Cells, Leading to Metastatic Disease - CU Anschutz newsroom, accessed September 11, 2025, https://news.cuanschutz.edu/cancer-center/covid-19-awaken-dormant-cancer-cells

COVID infection early in pandemic linked to higher risk of cancer death, CU study finds, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.unmc.edu/healthsecurity/transmission/2025/07/30/covid-infection-early-in-pandemic-linked-to-higher-risk-of-cancer-death-cu-study-finds/

Full article: The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Incidence and Short-Term Survival for Common Solid Tumours in the United Kingdom: A Cohort Analysis, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.2147/CLEP.S463160

Highlights from 2025 U.S. Cancer Statistics, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/united-states-cancer-statistics/publications/uscs-highlights.html

Impact of COVID-19 on 2021 cancer incidence rates and potential rebound from 2020 decline | JNCI - Oxford Academic, accessed September 11, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/jnci/article/117/3/507/7765196

Cancer statistics, 2025 : CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians - Ovid, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.ovid.com/journals/cajc/fulltext/10.3322/caac.21871~cancer-statistics-2025

Impact of COVID-19 on 2021 cancer incidence rates and potential rebound from 2020 decline | JNCI - Oxford Academic, accessed September 11, 2025, https://academic.oup.com/jnci/article-abstract/117/3/507/7765196

Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, featuring state-level statistics after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic - PubMed, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40257373/

Senolytics reduce COVID-19 symptoms in preclinical studies - Mayo Clinic News Network, accessed September 11, 2025, https://newsnetwork.mayoclinic.org/discussion/senolytics-reduce-covid-19-symptoms-in-preclinical-studies/

COVID-19 and chronological aging: senolytics and other anti-aging drugs for the treatment or prevention of corona virus infection? - Aging-US, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.aging-us.com/article/103001/text

Senolytic Therapies May Reduce COVID-19 Mortality in the Elderly - Contagion Live, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.contagionlive.com/view/senolytic-therapies-may-reduce-covid-19-mortality-in-the-elderly

Cellular Senescence and COVID-19 Long-Hauler Syndrome - Mayo Clinic, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.mayo.edu/research/clinical-trials/cls-20510125

Targeting senescent cells in aging and COVID-19: from cellular mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities - PMC, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11447201/

Metformin may reduce risk of long COVID by 64% in overweight or obese adults | CIDRAP, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/covid-19/metformin-may-reduce-risk-long-covid-64-overweight-or-obese-adults

Common diabetes drug metformin cuts long covid risk by 64 percent in UK study, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.news-medical.net/news/20250908/Common-diabetes-drug-metformin-cuts-long-covid-risk-by-64-percent-in-UK-study.aspx

Metformin cuts risk of long COVID by 40% in patients with obesity, trial suggests, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.livescience.com/health/coronavirus/metformin-cuts-risk-of-long-covid-by-40-in-patients-with-obesity-trial-suggests

Study Shows Metformin Lowers Long COVID Risk - UNC School of Medicine, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.med.unc.edu/medicine/news/study-shows-metformin-lowers-long-covid-risk/

Metformin and Time to Sustained Recovery in Adults With COVID-19: The ACTIV-6 Randomized Clinical Trial - PubMed, accessed September 11, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40658388/

Metformin on Time to Sustained Recovery in Adults with COVID-19: The ACTIV-6 Randomized Clinical Trial | medRxiv, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.01.13.25320485v1.full-text

Expert: Pharmacists Play Key Role in Addressing COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/expert-pharmacists-play-key-role-in-addressing-covid-19-vaccine-hesitancy

Counteracting Immunosenescence—Which Therapeutic Strategies Are Promising? - MDPI, accessed September 11, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2218-273X/13/7/1085